Tagged: history

Some forthcoming events I’m doing

Variously on music, politics and history – please come along if you’re interested.

Saturday 19th May: @CultishEvents playback of The Holy Bible at which I’ll be giving an introduction to the album and Triptych. Details: https://www.facebook.com/events/1503877846345865/

Saturday 2nd June: talking about music and misogyny in Under My Thumb: Songs That Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them, with the book’s co-editor Eli Davies and our contributors Frances Morgan and Anna Fielding. Details: http://stokenewingtonliteraryfestival.com/snlf_events/under-my-thumb/

Saturday 9th June: I’ll be explaining the early Victorian primitive rebellion known as the Rebecca riots as part of Chartism Day. Details: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/history/history-events-publication/chartism-day

Stuff I’ve done lately.

For New Humanist: The End of Work as We Know It? The gig economy, history, automation, grassroots workers’ organization and other possible responses to late-stage neoliberalism.

For Soundings: Music, Politics and Identity: From Cool Britannia to Grime4Corbyn. Basically Clampdown five years on.

For the Irish Times Women’s Podcast: Under my Thumb‘s co-editor Eli Davies and myself on the complexities of liking misogynist music.

And, for the excellent Desolation Radio, rambling on the Rebecca riots, Chartism, popular protest and radical history.

A pessimist is never disappointed

Having been wrong about the Brexit vote, and then wrong about Trump, I went into last week’s election with a sense of optimism that I knew full well verged on the perverse. I’m now trying to sort out what I based that optimism on, so here are some disjointed thoughts. Continue reading

One of the interesting moments – I wouldn’t call it a highlight – of Wednesday’s debate was when Nuttall threw the “taking us back to the Seventies” canard at Corbyn and a large part of the audience responded with immediate vocal contempt. I don’t know if it was simply a recognition of that line as part of lazy and condescending scaremongering – see also “magic money tree” and Amber Rudd’s bizarre idea of what a game of Monopoly entails – or if it means the recent questioning and debunking of several myths of “the Seventies” are gaining traction, or if the audience was just young enough that the Seventies mean little to them, or if we’re at a point where the changes in geopolitical context since “the Seventies” are so glaring as to render such a reference to them absurd.

On Enemies Within: growing up with the Miners’ Strike in memory, myth and history

“Faced with possible Parliamentary destruction of all that is good and compassionate in our society, extra-parliamentary action will be the only course open to the working class and the Labour movement.”

– Arthur Scargill, 1983

“We’re secure in the knowledge that we already lost a long time ago.”

– Richey James, 1992

I knew the death of Margaret Thatcher wasn’t likely to usher in a Truth and Reconciliation Commission on the Eighties, but it’s been good to see the thirtieth anniversary of the Miners’ Strike pass this year and last with due commemoration, and with little attempt to present what happened as a good thing.*

A few months ago I went to a screening of Still The Enemy Within.** This documentary does a fine job of detailing the strike’s background and bringing the experience of the strike to life. Generally I avoid (resist?) revisiting the strike in quite such unflinching detail, because – and apologies if this sounds hyperbolic; it isn’t – I find doing so almost debilitating, as though nothing else matters outside of emphasising how permanently shattering its results have been for a huge part of this country. The depth of feeling can be such that you want to back away from the edge. At this stage, at this distance, all one can do is bear witness. All one can do is testify.

(Every time I try to write about the Miners’ Strike and its aftermath, the exercise turns out to be merely a scraping at the surface, an unsuccessful attempt to uncover the heart of the matter. It’s a gradual stripping away of layers, on my part, of bravado and defensiveness and fatalism. This post won’t be definitive either. I want to do the thing justice, to give it adequate weight, and I know I can’t, so this will have to do. For the purposes of this piece, in any case, the strike is less of a conclusion and more of a jumping-off point.)

In its uncompromising commitment to telling a bleak and unrelenting story, Still The Enemy Within is a necessary supplement to something like Pride. The strike deserves to be remembered in the latter’s upbeat and uplifting terms of solidarity, sure, but equally what deserves remembering is that there were no happy endings, nothing of what we learned in the Nineties to call emotional closure. (Hoho, the only things that got closure in the Nineties were more of the pits.) There are wider questions here about what counts as history, and whether history must be necessarily cool-headed and objective, not relieved by colour or comedy or complicated by messy, judgement-clouding emotion. But the tangle of story and history surrounding the strike suggests that the event and what it stood for are not “just” history yet. Like Hillsborough in 1989, Brixton in 1985, Toxteth in 1981, the Miners’ Strike is a flashpoint that unforgivingly illuminates its era. That Eighties hot war of government against people still hasn’t cooled.

You may imagine how exceptionally bored I was as a post-industrial Nineties teenager. (I mean, I couldn’t even join a brass band.) Growing up, before I ever knew I wanted to be a historian, I wanted to understand history – both its grand outlines and its bathetic, personal confines in which I knew my community to be stuck. How did we get here, and why? Growing up I felt stymied and stifled by history, and had the consequent compulsion to dig beneath the surface for the story. What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow, out of this stony rubbish? Continue reading

Plus ça change

“At some meeting about that time of statesmen – in Paris or Geneva – a French black-and-white artist said to me ‘I am by profession a caricaturist, but here photography suffices’. It struck me as poignantly true then, and has often so struck me since. Reality goes bounding past the satirist like a cheetah laughing as it lopes ahead of the greyhound.”

– Claud Cockburn, c.1939.

“Pride”, identity and intersectionality

An extended version of what I wrote for the New Welsh Review.

From a certain angle of rose-tinted retrospect, Britain in the 1980s is a storyteller’s dream. In the past few decades, British films like Billy Elliott, Brassed Off and The Full Monty have presented the era as one of struggle and defeat for the British working class, with Margaret Thatcher as a grotesque presiding nightmare. Counter-accounts of Thatcher’s rise — notably 2012’s The Iron Lady — have revolved around the victory of the country’s first female Prime Minister over a male-chauvinist political establishment and the macho thuggery of Britain’s trade unions. There has been less cultural coverage of the stories that unfolded in the margins of this grand narrative. Matthew Warchus’s film Pride is distinctive initially for its focus on those at the frequently forgotten intersection of 1980s conflict.

For audiences outside the UK, and even some within it, the details of the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 are unknown or hazy at best. The ideological clash between the Thatcher government and the National Union of Mineworkers became a titanic struggle for the survival of the British coal industry, played out in mining communities up and down the country in a year long strike. Against the NUM, the Thatcher government deployed an unprecedented degree of police violence, media bias and state surveillance, the extent of which is only recently coming to light. Popular support for the strikers, meanwhile, was generated both by instinctive anti-Tory sentiment and an awareness that the miners were the front line of resistance to a right-wing assault on the economic, political and social fabric of Britain. If the miners were beaten, then sooner or later little of the postwar welfare settlement would be left intact. That they were beaten, and that NUM leader Arthur Scargill’s jeremiads on the triumph of neoliberalism have indeed come to pass, is part of why the strike retains its peculiar status as a cultural and political touchstone in Britain, and why it still has the ability to provoke powerful and frequently bitter reactions both for and against.

If considered purely in terms of popular resistance to neoliberalism’s shock-troops, Pride could be dismissed for pulling its punches, since it shows little of the high political stakes invested in the outcome of the strike or the police occupation, brutality, and harassment to which mining communities were subject. But this is not quite the task it sets for itself. Directed by Matthew Warchus and scripted by Steven Beresford, Pride tells the story of the London-based activist group Lesbians and Gay Men Support the Miners, and their encounters with a group of striking miners from the Welsh coalfield. It’s a true story, though you’d be forgiven for remaining unaware of this until the closing credits, and, like many depictions of the 80s, its dramatic narrative seems almost too good to be true. The strike itself becomes a backdrop to the staple fare of feel-good film: gently comical culture-clashes, personal journeys and gently triumphant coming together in the face of adversity. Where Pride manages to be more than the sum of its parts, however, and where it becomes a particularly useful intervention into contemporary debates, is in its unabashedly political edge.

In advance of the Manics’ anniversary tour of The Holy Bible, the Cardiff production company Barefoot Rascals is making a short documentary on the album’s history and its impact on fans, involving interviews with Simon Price, myself and others. To get the film produced, we are asking for funding on Kickstarter – please donate a couple of quid here if you can. We are halfway to meeting the funding target so far.

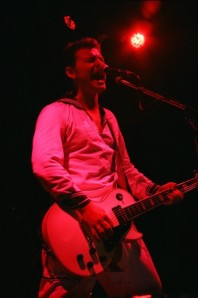

Below is a guest post and pictures by former music photographer Lorna Cort, who remembers the original album tour in 1994 and whose pictures will be used in the documentary.

The Manic Street Preachers were my life. After discovering Stay Beautiful in the Summer of 1991 I’d followed tours, collected just about everything, written too many letters to James, learned to play guitar ( a white Gibson Les Paul obviously!) and helped form the band of fellow Manics fans ‘Dead End Dolls’.

By 1994, I bought a camera and decided I was going to be a music photographer. I can’t remember who gave me a photo pass for Portsmouth Guildhall on 12th October but thank you, I have treasured the results. Back in the olden days of film and developing at Boots, I had no idea how the photos would turn out. As well as manual focus I had to contend with stage divers flying overhead, security guards taking up all the room in the photo pit, and the deafening sound of a thousand screaming fans 2 feet behind me and the flimsy barrier! The gig was over in a flash, I remember James raised his eyebrows ‘hello’ at me, the white sailor suit looked amazing under the lights, the sound was incredible, I wanted to sing along but no, I was a photographer… I couldn’t look like I was actually enjoying myself!

The Holy Bible was a challenge to listen to, it was at times uncomfortable, shocking, it was emotional… and it was perfect. When I look at my photos 20 years later I see the concentration on James’ face, the determination to get all the words out, Nick’s anonymity, head down with a nose-skimming fringe, and I see how painfully skinny Richey’s arms look, and that he has the word ‘LOVE’ written in black marker on his fingers. They were so beautiful, so focused.

I wanted to be part of The Holy Bible – My Testament to share my photos with old fans and new, to celebrate one of the most amazing records ever created and to remember the excitement and love I had for this band. To paraphrase Nick – they remain the most intelligent people I ever met in my life. I so hope this project goes ahead and maybe brings the Holy Bible to new listeners. Thank you.

Bonnets and Bolshevism

1. For my next trick in the arena of niche overthinking-it monographs, I am going to be writing a book on the Rebecca riots. There have already been magisterial studies of the movement which have focused on its political and economic aspects, but I am going to look at its social and cultural aspects, and the ways in which it had more variety, more politics, and more of Old Weird Wales than is generally acknowledged.

To include: why there was a bit more to the movement than hill-farmers smashing up tollgates in bonnets, petticoats and false beards; the nature of Welsh resistance to early industrial capitalism (as touched on in this post); contemporary ideas of gender and the early Victorian undermining of female social and sexual agency; how Rebecca’s image became a national ‘idiom of defiance’ – basically, a meme – and wider issues hopefully relevant to today, eg “rough” versus “respectable” protest; the traditions of masked and anonymous protesting; and how popular culture can be integrated into popular resistance.

Don’t worry, I’m fully aware that this book will be of interest to about four people at a push.

*

2. The last time I was in the House of Commons in any official capacity, I was taking students to lobby against the introduction of top-up fees. Our side having narrowly lost that vote, I then got massively drunk in the ULU bar, decided to give up student politics as a mug’s game, ranted at a Sky News crew and eventually had to be carried out to a taxi by members of my delegation.

Last month I attempted to conduct myself with greater dignity, and spoke on this Zero Books panel. Strike! magazine wrote up the evening here.

Intersectional Feminism, Class, and Austerity

Last week I went to a conference at Manchester Met to speak (broadly) on intersectional feminism, alongside the excellent Reni Eddo-Lodge. The event had some useful and interesting contributions, given in an atmosphere notable for constructive and supportive discussion, and for critiquing work done previously rather than seeking to reinvent the feminist wheel. Below is a transcription of the talk I gave. It works as both a synthesis of things I’ve written previously on feminism and class, and as a step towards articulating how my own type of feminism developed (clue: this year it’s thirty years since the Miners’ Strike). It also, in a personal best, contains only one use of ‘autodidact’, none of ‘hegemony’, and no mention of the Manic Street Preachers.

Introduction

The concept of intersectionality has a long history, and has informed the political work of women from Sojourner Truth in 1851 to Selma James’s 1975 pamphlet ‘Sex, Race and Class’. In 1989 Kimberlé Crenshaw’s use of the term emphasised how women of colour experience multiple systems of oppression, and how their experiences and voices are frequently marginalised or erased, even within feminist or anti-racist discourses which aim at justice or liberation. Intersectionality has been the subject of much recent discussion within feminism, some of which has dismissed the concept on the grounds of its supposed academic obscurity and irrelevance to ‘ordinary’ people. I will dispute this dismissal.

The aspect of intersectionality I’ve written most about is the tension between class politics and some of the ways in which contemporary UK feminism is expressed. I’m not suggesting that class is the only dimension of oppression, or the only one worth exploring, but I do see class as something fundamental, and as something which intersects significantly with both race and gender. These interactions are particularly visible in the debate on ‘chavs’, which I see as a point at which class prejudice crosses over with several others. I will look at that debate and at the surrounding context of neoliberalism and austerity in which it takes place. I will then look at how responses to this debate, in attempting to rehabilitate working-class identity, have instead constructed exclusionary models of class based around the idea of the white male worker. I will then finally talk about how the calls for feminism to make itself accessible beyond white and middle-class women, has tended to involve negative or condescending assumptions about working-class women and their capacity for education, political consciousness and organisation.

Things I’ve written elsewhere:

- For the Wales Arts Review, What Riot Grrrl Did and Didn’t Do For Me: on female artistic expression, theory vs practice, post-punk, class and feminism, the 90s, adolescence, and Courtney Love, I think that’s everything.

- For Planet on the centenary of the Senghenydd colliery disaster, a piece about the issues it continues to raise around Welsh identity and the history of working-class exploitation and resistance.

The Manics’ Next Step

We cannot get rid of employers and slave-driving in the mining industry, until all other industries have organized for, and progressed towards the same objective. Their rate of progress conditions ours, all we can do is set an example and the pace.

– The Miners’ Next Step (1912)

Nicky Wire in the Quietus reviews (previews?) Rewind The Film.

Of course, having put away excitement and belief and other childish things, I no longer await a new Manic Street Preachers album with the same starry-eyed avidity I once did. (Do you?)

On the title track and its accompanying video, I liked what Lost Communication had to say:

… and I’d add only that the swampland that lies between mawkishness and sentimentality is a thoroughly Welsh place to get stuck. On at least one of the tracks discussed in the Quietus interview, though, ‘30 Year War’, the band seem to succeed in side-stepping the rose-tinted ‘noble decline’ trap:

“It’s not about Thatcher, it’s definitely about Thatcherism, about the establishment across the last 30 years, and it doesn’t matter what government is around, we always love to portray ourselves as this holier than thou country, and yet we have scandal after scandal uncovered, right to the root of power, government, Murdoch, the police, Hillsborough, this stupification of the class I grew up in, which I think all stems from Thatcherism really. The idea that if you break down any power that we had we’re going to be fucked forever…

I find that elitist, ‘We know what’s better’ is so all pervading, from the monarchy to fucking Cameron to Mumford and Sons. We’re just told… what did one of Mumford and Sons say the other day? ‘Either ignore it or celebrate it.’ What a fucking futile attitude. Don’t say anything bad, just ignore it or celebrate it. So what about fascism then? We don’t like it, we’ll just ignore it. It does feel like the last five years has been such a redress of monarchy and establishment and public school through all points of our culture. I feel a bit helpless about it.”

Bang on, of course, as is everyone else who appears to be waking up and wondering what went wrong after the Old Weird Nineties (that Mumfordian ‘ignore or celebrate’ ultimatum is straight outta Cool Britannia, although much of that era was more notable for its ability to do both at once).

I’m glad that bullish bullshit detector of his endures to an extent. It’s encouraging that the disingenuous and damaging nature of both austerity and austerity chic is being increasingly noted, but the lack of analysis and alternatives are still too glaring for this to be any more deeply gratifying. Not that analysis or alternatives have ever been the preserve or the responsibility of rock stars.

Seizing the Dydd.

The Wales Arts Review takes an interesting and optimistic shot at galvanizing the cultural future of the country. I found it sobering to contrast this overview, which looks forward from within, with the hellishly depressing one contained in another recent article called ‘The unbearable sadness of the Welsh valleys’. This does exactly what it says on the tin: an external observer tracks the Valleys’ economic decline, and its social and cultural impact, in what sometimes reads like a negative version of the Victorian travelogues which eulogised the beauties of the Welsh landscape (and largely overlooked their quaint but inconvenient inhabitants).

Without wishing to damn with faint praise, I’ll take that second article over MTV’s The Valleys, although its paternalist hand-wringing and lack of solutions make about as much constructive contribution. As I concluded after my own incoherent trawl through my fatherland’s history and identity, focusing on an oversimplified, often romanticised past, however grievous and traumatic its loss, produces only stasis and resentment. We need to move past this, even at the risk of losing what little identity we have (and it’s currently an overwhelmingly negative one, at best pitiful and at worst exploitative and sensationalist). This needn’t automatically mean considering oneself part of, as the Wales Arts Review‘s very good article has it, ‘a generation unscarred by the battles of the past’ – any product of the south Welsh coalfield, as of other parts of post-industrial Britain, is thoroughly scarred by the battles of the past and knows themselves to be. But it does mean that these scars needn’t be one’s defining feature, in one’s own view or that of outside observers.

The problem is, of course, that it’s one thing to move forward in terms of arts and culture, but socio-economically speaking it’s quite another.

Radical History: the London Corresponding Society vs the Privy Council, 1794

The long essay linked here is something I wrote years and years back, as an undergraduate, and I have finally now got round to finding somewhere useful for it to live online. It is set at a time, in the late 18th c. Britain made famous by Blackadder the Third, of a rise in popular radicalism, political organisation by artisans and labourers, and campaigns to extend the franchise. The essay looks specifically at the process, in many ways unprecedented and bizarre, whereby organisers of, participants in, and vague or occasional sympathisers with campaigns for popular democracy were rounded up and questioned by the highest echelons of a hostile, uncomprehending and paranoid state. (Think the Thatcher cabinet doggedly interrogating not only the NUM leadership but also the whole audience of a Coal Not Dole fundraiser, or, idk, the present cabinet interrogating UK Uncut.)

Like many things which can be given that kind of build-up, the actual material of the interrogations can be a surprisingly dull read, but there were several aspects that I found, and hopefully the general reader will find, of interest, amusement, and continued relevance, viz:

To begin with, despite the mass arrests of radicals being justified by panicky accusations of treason, this accusation wasn’t a comfortable fit with the evidence. Treason in 1794 specifically related to plotting against the reigning monarch rather than the government, and the societies agitating for popular democracy, despite a preoccupation with Revolutionary France, were invariably concerned more with the latter than the former. The 1794 interrogations and the trials which followed, however, were an abrupt step in a long-term shift of the legal location of sovereign power towards Parliament, in which the extra-parliamentary advocacy of constitutional change became construed as a treasonable practice. In 1795, the new Treason Act defined as traitors not only all those who ‘compassed or devised’ the death or deposition of the monarch, but also those seeking ‘to intimidate or overawe both Houses or either House of Parliament’.

Relevant today? Take your pick. My thanks to the John Thelwall Society, who are great.

Talking Treason? John Thelwall and the Privy Council examinations of the English Jacobins, 1794

* E P Thompson: “But for spies, narks and letter-copiers, the history of the English working class would be unknown.”

** M. Philp, ‘Intrusions’, History Workshop Journal, 65 (2008), pp. 220-7

Little Empires V: Coming Up For Air

This is the fifth AND LAST in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Three: Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes

Part Four: Everybody Hates a Tourist

Part Five

“For a start, the very fact that we were Welsh meant that we had to try 100 times harder than any other group. Even now, in some terrible news magazine, someone’s reviewed the album and the headline is ‘Boyos To Men’. And I’m not saying it’s racist or anything: I just find it incredibly thick. In a way I’m glad I’ve got all that now: it gives me something to rail against, to use as a creative feeder.”

Can you speak any Welsh?

“We were never allowed to learn. And that’s another big bit of resentment in us: it wasn’t on the curriculum for the whole of South Wales. I’d have loved to have been able to speak Welsh.”

“Damn it all, you can’t have the crown of thorns and the thirty pieces of silver.”

– Aneurin Bevan, c. 1956

After all this, I mean, I still feel Welsh, and I still call myself it. ‘Welsh’ for me can be a residual, reserve identity, buried or submerged, but still enduring; something to cling to when adrift, rightly or wrongly; something to anchor me. What the identity consists of, though, I’ve never been sure. It’s not a national identity but a local one, and its localness – the ways in which I feel myself to be Welsh -always keeps me conscious of the ways in which I’m not. Rather than ‘yes, that’s it’, it’s easier to say ‘yes, but that’s not all it is’. Wire in that 1997 interview may well proclaim himself ‘into oneness’, but there is no One Wales. Even beyond the country’s linguistic, geographic and political divisions, there exist multiple fractured identities, defining themselves by the local not the national – particularly through being from X, rather than from Cardiff. Growing up, attributes, accents and attitudes were associated with specific areas, towns, areas of towns, sometimes pinned down to exact streets. The Wales of swords and stone circles, drowned lands, dragons and druids, Taliesin and Eisteddfodau exists in romance alongside the reality of GLC’s Newport, Gavin & Stacey’s and Simon Price’s Barry Island, the drug-soaked, politically corrupt underworld of Lloyd Robson’s Cardiff Cut, the Valleys anti-romances of Rachel Trezise, and a multitude of other identities scattered and self-contained but highly secure in their specifics. To brush under the national carpet all of these peculiarities, to smother them in fantasies of ancient racial purity, the flag, the Senedd, or MTV’s predictably execrable The Valleys, does justice to nothing Continue reading

Little Empires IV: Everybody Hates a Tourist

This is the fourth in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’. Stay tuned with suitably low expectations.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Three: Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes

Part Four

To be Welsh is to be conscious

At dusk of the spilled blood

That went into the making of the wild sky…

And an impotent people,

Sick with inbreeding,

Worrying the carcass of an old song.

– ‘Welsh Landscape’, R S Thomas

To be born Welsh is to be born privileged

Not with a silver spoon in your mouth

But music in your blood and poetry in your soul

– from ‘In Passing’, Brian Harris

While living in London I had that second quote on a keyring for several years; if you’re Welsh, you might have done so too – or you might have had it on a mug, a teatowel, an embroidered sampler. The 1967 poem from which it is (mis)taken contains far bleaker Thomas-esque currents (‘ugliness that scars the spirit / as the earth’, ‘rivers of mingled blood and sweat’), but this opening snippet has become both tourist branding, found everywhere it can be sold, and a kind of faux-folk fetish for the Welsh themselves. With its elevation of ‘natural’ cultural creativity over material advantage making a virtue of necessity, it is our Keep Calm and Carry On – a comforter, a pacifier. Continue reading

Little Empires III: Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes

This is the third in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’. Stay tuned with suitably low expectations.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Three

The furies are at home

in the mirror; it is their address.

Even the clearest water,

if deep enough can drown.

Never think to surprise them.

Your face approaching ever

so friendly is the white flag

they ignore. There is no truce

with the furies. A mirror’s temperature

is always at zero. Its camera

is an X-ray. It is a chalice

held out to you in

silent communion, where gaspingly

you partake of a shifting

identity never your own.

– ‘Reflections’, R S Thomas

Most people see me as a rake, womanizer, boozer and purchaser of large baubles. I`m all those things depending on the prism and the light. But mostly I’m a reader.

– Richard Burton

Besides the drowning of Tryweryn, Ready for Drowning also snags the idea of drowning one’s sorrows, referencing the alleged propensity of the Welsh for – what shall we call it? – a steady, a committed, a co-dependent relationship with drink. The association of Wales with a certain kind of romanticised and spectacular inclination to alcoholism – not so much in reality as in legend – still persists. Ready for Drowning compares the flooding of Tryweryn with how, according to Wire: ‘a ceaseless chain of Welsh people seek to adjust to their circumstances by drowning their synapses in alcohol. …‘it’s half Richey, half Welsh identity – about how many of our icons either drink themselves to death or run away’. Continue reading

Little Empires II: Fear Death By Water

This is the second in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’. Stay tuned with suitably low expectations.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Two

In the Bible, God made it rain for 40 days and 40 nights. That’s a pretty good summer for Wales. That’s a hosepipe ban waiting to happen… I was eight before I realised you could take a cagoule off.

– Rhod Gilbert

O where are our fathers, O brothers of mine?

By the graves of their fathers, awaiting a sign…

The slopes of slag and cinder

Are sulking in the rain

And in derelict valleys

The hope of youth is slain.

– from Gwalia Deserta, Idris Davies (1938)

Idris Davies, the coalfield’s ‘bitter dreamer’, lost a finger in a mining accident and was first radicalised and then disaffected by his participation in the 1926 General Strike. Subsequently unemployed, and having been introduced to the work of Shelley by a fellow miner, he began four years of what he called ‘the long and lonely self-tuition game’. In his poetry, as fanboyed by T S Eliot, he is notably attached to the word ‘derelict’, especially as a description of the south Welsh valleys, desolate and desecrated by industry. (They’ve only grown more apt as a pairing.) Davies has little of R S Thomas’ brutally bleak, at-bay snarling; his jeremiads are, like the landscape and land he describes, just ‘sulking in the rain’, sad and sullenly resigned. Continue reading

Little Empires: on Wales, history, identity, and the Manic Street Preachers

‘I’ve never written about Welsh identity before: these days, I’ve got to search for things to write about, whereas in the past everything would be driven by anger and all the rest of it. Now I’ve got to delve more… Ready For Drowning is the most complete song I’ve ever written, I think…’

One: All Surface No Feeling

Tree stumps exposed by low water levels of the Llyn Celyn reservoir. Its construction in the early 1960s involved the flooding of the Tryweryn valley and the drowning of the village of Capel Celyn.

“The submerged land of Cardigan Bay is called Cantre’r Gwaelod (‘the lowland hundred’). It was defended from the sea by an embankment and sluices. Seithennin was keeper of the sluices, and one evening when there was a great banquet he became drunk and left the sluices open. The water rushed in and drowned the inhabitants. The poet Taliesin was the only one to escape alive.

“When man first came to live on the coast of Wales (sometime between the Neolithic and the Iron Age), the sea level was still rising between Wales and Ireland, separating the two countries further and further, and the legend relating to the drowning of the Lowland Hundred probably developed as a result of folk-memory of a sudden coastal flooding many centuries ago. The remains of peat and tree trunks which are visible on the beaches when the tide is far out further captured man’s imagination. Similar traditions are connected with certain Welsh lakes [and] with other parts of the Welsh coast… The moralistic and onomastic elements in all these traditions are very obvious.”

– Robyn Gwyndaf, Welsh Folk Tales (1989)

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish?

– from The Wasteland, T S Eliot (1922)

Lately I’ve been revisiting both the land of my birth and upbringing and mid-period Manic Street Preachers. The latter was a moderately painful process which has, incidentally, left me staggered all over again that ‘Tomorrow Steve Ovett has injured his calf’ was considered to pass muster as a lyric. I don’t generally subscribe to the idea that everything good about the band vanished along with Richey; I think Design for Life is, while maybe not the best thing they’ve accomplished, at least the most valedictory, the thing I remain most proud of them for doing. But yeah, they should perhaps have called a halt to things shortly after that. Continue reading

Radical history: the Scotch Cattle rebranded

In my former life as a shiftless, rootless, and economically useless humanities student, I researched and wrote on weird, failed, disreputable and consequently marginalised or forgotten moments in the history of popular resistance to industrial capitalism – food riots, rough music, cross-dressing and animal masks, legendary figureheads (Ludd, Swing, Rebecca) and the use of theatre, symbol and spectacle. My guiding principle was that eighteenth and nineteenth-century protest often contained a popular symbolic and ritual repertoire adapted for the purposes of expressing discontent, and that it also made visible an increasing conflict between established popular custom and the nascent doctrines of industrial capitalism and constitutional law. Some of what I wrote is here, though it’s not very good.

If you’ve never read about any of this then you ought, it’s great. E P Thompson’s concept of a ‘moral economy’ motivating collective social and economic protest – the idea of a continuous extra-parliamentary and extra-legal tradition based on an appeal to established popular rights, which juxtaposed natural and social justice with prevailing civil and criminal laws – still finds expression where it has to, from ‘proletarian shopping’ to the ideas of social justice expressed through ‘rough music’ in the recent kickings-off in Montreal and Quebec. I mean, one might be tempted to conclude that the increasingly visible powerlessness of the average citizen to exercise opinion by constitutional means has encouraged a return to more immediate and hands-on methods of collective bargaining.

Anyway, the Scotch Cattle – an early attempt at industrial organisation in 1820-40s south Wales – are obscure and getting obscurer: one monograph, a couple of local history articles, and minor mentions here and there, usually with audible disapproval. The Scotch Cattle tend to be dismissed in traditional histories of labour and of Wales, due to their failure to fit neatly into narratives of either the sober and respectable growth of trade unionism or the development of an orderly Welsh society. This is a large part of what interests me about them and others like them, though they are also fascinating on their own terms, being at once an obvious and logical response to the conditions of early industrial capitalism, and peculiar as fuck.

Much to my own surprise, I have an article on the Scotch Cattle published in this month’s Welsh History Review – I presume out now, or impending. My take on them is that they are a hybrid movement, representing the attempts by workers to transfer their accustomed techniques of pre-industrial protest – yer basic charivari – to the untested environment of the south Welsh coalfield in its wild and brutalising stage of development (in Gwyn A. Williams’ useful phrase, its ‘frontier years’). Divorced from their original context and the social relations on which they depended, these techniques were open to mutation and fragmentation, and their effective operation was no longer guaranteed, with less than hilarious consequences.

That’s what my research has led me to conclude, at least. Throw in proto-class war, contested constructions of masculinity, and the old ritualised ultraviolence, and you’ll be unsurprised to learn that my application for AHRC funding got turned down three years on the trot.

Standard, and Poor.

Privatize everything > Occupy the tollgates.

You’re all joking about the roads being next for privatization, aren’t you. Aren’t you. Oh, you’re not.

It’s just that in another lifetime, one of toil and blood, I did my whole thesis about a little local difficulty which centred around privatized road networks: the ridiculous/amazing “Rebecca riots”.

Part of what I liked about the study of history was that it did occasionally seem – by no means always, of course – as though society in general wasn’t too disparate, atomized, hopelessly confused, thick, or arrogant to learn from its mistakes.

For example: ‘Wow, at least private roads wouldn’t be an option /these days/’, I’d often muse, back in the day, having conducted hours of research and written thousands of words about how badly it had all worked out in the face of popular insistence upon public utilities being kept for the collective good rather than left to the profiteering of incompetent private companies.

(The Rebecca riots were a lot more complex than that, obviously, hence my studying them in the first place, and my bringing in their use of masking, cross-dressing, ritually smashing stuff, inter-class cooperation, liminal states, gender essentialism, and the disparity between lived experience and political and media discourse – don’t worry, neither the Taxpayer nor Hard-Working Families were paying for me to study any of this – but the general resentment of private ownership as leading to general neglect and profiteering holds true as a contributing factor – as indeed it holds true over two hundred years on.)

I’m sick of saying we’re being taken back to the Victorian age, but this? Is the government just trolling, now?

Or, with less (or perhaps more) conspiracist fervour: RT @bengoldacre Wouldn’t it be a shame if this distant roads nonsense distracted you from the Lords’ final vote on #NHSbill.

On Thatcher: Icons and Iron Ladies.

A spectre is haunting London. My daily commute, never a joyful affair, has recently been granted a further dimension of irritation by adverts on buses, hoving into view with tedious regularity, bearing the image of Meryl Streep dolled up as Mrs Thatcher in The Iron Lady. Thirty years on from her rise to power, and after a minor rash of small-screen depictions – Andrea Riseborough in The Long Walk to Finchley, Lindsay Duncan in Margaret – Streep will now portray her on the big screen, the prospect of which I could have happily lived without.

Having as I do firsthand experience of Thatcher’s impact, her government’s break with prevailing consensus and bloody-minded devotion to neoliberal orthodoxies, an objective and rational evaluation of the woman is probably beyond me. That said, her presumably impending death, although I do have a longstanding appointment at a pub in King’s Cross to dutifully raise a glass, is something I’ll be largely indifferent to. It won’t matter. Thatcher as a person has far less bearing on the current world than what she represents. The damage has been done, the battle lost, and much as I might appreciate a Truth and Reconciliation Commission into the 1980s, Thatcher and her co-conspirators are by now too old and whiskey-soaked to be held to any meaningful account.

Efforts to humanise Thatcher, even when they enlist Meryl Streep, seem discomfiting and deeply bizarre. What she means has transcended what she was, is and will be. The purpose of this post, therefore, apart from being an exercise in detachment for me, is to look briefly at some aspects of Thatcher’s image in political and pop culture, the effect of her gender in her role as a woman in power, and her political legacy. Quick, before the next bus goes past.

Revolting Women, a History.

Written a while back to kick off Bad Reputation’s series on women in protest. Reposting it has mostly reminded me of how fast politics is moving now.

Last winter’s wave of student and youth protests held many points of interest, but one of the most amusing was the Daily Mail’s pearl-clutching front page on what it chose to call Rage of the Girl Rioters, in which it claimed that ‘rioting girls became the disturbing new face of violent protest’. While the article betrayed anxieties about social protest in general, the inclusion of visible female agency occasioned a particularly salacious shock. Continue reading

The Pits and the Pendulum

I’ve had coalmining on my mind recently. Contra last week’s Metro, I don’t think it’s accurate to say ‘the world looked on in despair’ at events at Gleision Colliery – in fact the story was predictably underreported and largely unremarked upon by my usual social media circle, until the story became a self-evidently human tragedy, whereupon it was hardly engaged with at any deeper level than that. Anyway:

As the admittedly lame title of this blog suggests, the coalmine for me is bound up with a certain sense of national identification, but also, if not more so, with class and regional associations. I feel that I have more in common with someone of my age from a post-industrial area in (say) south Yorkshire, than I might with someone from rural west or north Wales or indeed the great bright-lit sprawl that is Cardiff and the Vale. Weighted against this potentially mawkish shoulder-to-shouldering with other unemployment blackspots is the knowledge that this landscape as a functioning entity, as something that defined one as part of and in relation to a certain workforce, as the sum of one’s labour, has (been) altered out of all recognition and what it tends to be seen as generating now is dysfunction. But the mine as a symbol of shared frames of reference carries an inescapable emotional weight. Continue reading

Sunday Service: ‘Twas the Riot Before Christmas

If you’re an easily suggestible sort, the last few weeks’ flurry of alarmist headlines on strikes, snow, and student riots might lead you to think of London as the convulsing epicentre of the end of the world as we know it. In fact, it’s still perfectly possible to work and play on the streets of the capital without detecting any signs of the collapse of civilisation, although that doesn’t mean they aren’t there.