Tagged: wales

Stuff I’ve done lately.

For New Humanist: The End of Work as We Know It? The gig economy, history, automation, grassroots workers’ organization and other possible responses to late-stage neoliberalism.

For Soundings: Music, Politics and Identity: From Cool Britannia to Grime4Corbyn. Basically Clampdown five years on.

For the Irish Times Women’s Podcast: Under my Thumb‘s co-editor Eli Davies and myself on the complexities of liking misogynist music.

And, for the excellent Desolation Radio, rambling on the Rebecca riots, Chartism, popular protest and radical history.

“Pride”, identity and intersectionality

An extended version of what I wrote for the New Welsh Review.

From a certain angle of rose-tinted retrospect, Britain in the 1980s is a storyteller’s dream. In the past few decades, British films like Billy Elliott, Brassed Off and The Full Monty have presented the era as one of struggle and defeat for the British working class, with Margaret Thatcher as a grotesque presiding nightmare. Counter-accounts of Thatcher’s rise — notably 2012’s The Iron Lady — have revolved around the victory of the country’s first female Prime Minister over a male-chauvinist political establishment and the macho thuggery of Britain’s trade unions. There has been less cultural coverage of the stories that unfolded in the margins of this grand narrative. Matthew Warchus’s film Pride is distinctive initially for its focus on those at the frequently forgotten intersection of 1980s conflict.

For audiences outside the UK, and even some within it, the details of the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 are unknown or hazy at best. The ideological clash between the Thatcher government and the National Union of Mineworkers became a titanic struggle for the survival of the British coal industry, played out in mining communities up and down the country in a year long strike. Against the NUM, the Thatcher government deployed an unprecedented degree of police violence, media bias and state surveillance, the extent of which is only recently coming to light. Popular support for the strikers, meanwhile, was generated both by instinctive anti-Tory sentiment and an awareness that the miners were the front line of resistance to a right-wing assault on the economic, political and social fabric of Britain. If the miners were beaten, then sooner or later little of the postwar welfare settlement would be left intact. That they were beaten, and that NUM leader Arthur Scargill’s jeremiads on the triumph of neoliberalism have indeed come to pass, is part of why the strike retains its peculiar status as a cultural and political touchstone in Britain, and why it still has the ability to provoke powerful and frequently bitter reactions both for and against.

If considered purely in terms of popular resistance to neoliberalism’s shock-troops, Pride could be dismissed for pulling its punches, since it shows little of the high political stakes invested in the outcome of the strike or the police occupation, brutality, and harassment to which mining communities were subject. But this is not quite the task it sets for itself. Directed by Matthew Warchus and scripted by Steven Beresford, Pride tells the story of the London-based activist group Lesbians and Gay Men Support the Miners, and their encounters with a group of striking miners from the Welsh coalfield. It’s a true story, though you’d be forgiven for remaining unaware of this until the closing credits, and, like many depictions of the 80s, its dramatic narrative seems almost too good to be true. The strike itself becomes a backdrop to the staple fare of feel-good film: gently comical culture-clashes, personal journeys and gently triumphant coming together in the face of adversity. Where Pride manages to be more than the sum of its parts, however, and where it becomes a particularly useful intervention into contemporary debates, is in its unabashedly political edge.

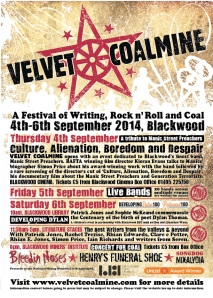

Velvet Coalmine, the festival: in Blackwood, 4-6 September

The first Velvet Coalmine Festival, featuring the best of Valleys music, art and literature, will be happening next weekend. Like Camden Crawl, but with more coal.

Among loads of other acts, I will be talking to the excellent Rachel Tresize about the ins and outs of having been a female Manics fan.

“Velvet Coalmine aims to create a platform for music, writing and ideas in the Blackwood area that allows our voice to be heard and celebrated. It allows our stories to be told and communicated to the wider world without censorship and our cultural heritage and identity to be expressed on its own terms without interference, without suppression and without agenda. The history of the Valleys is littered with exploitation, neglect and indifference but has proved a birthplace to a myriad of thinkers and pursuers of social justice and in an era when Old Etonian privilege continues to shape and influence decision-making and politics in the UK, creating an arts festival influenced by the radicalism of the 1984-85 miner’s strike and the Centenary of the Senghenydd mining disaster feels both timely and appropriate.”

Full listings and contact details can be found here on the website. Come on down.

Links to things I’ve written elsewhere.

1. ‘Crumbling Pillars of Feminine Convention’ – on Viv Albertine’s memoir Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys. Sex, punk, feminism, the usual.

2. ‘Living Fast: Revisiting Oasis’ Definitely Maybe‘ – on Alex Niven‘s Oasis; 90s Britain (bad) and 00s Britain (slightly worse); pros and cons of ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’ as life philosophy.

3. Retrospective on the 20th anniversary (!) of The Holy Bible, the summer of 1994 and the travails of being a teenage girl, available in the new issue of Planet magazine. Well worth buying a hard copy as it also contains, among other things, a fascinating article on the history of cross-dressing in protest. My piece is accompanied by the photo below, taken some time in the mid-90s when I had taken to hand-spraying a glittery hammer-and-sickle onto my dress, as was the style at the time. Outfit is not currently, as one correspondent suggested, housed in the museum of Welsh folk art.

Bonnets and Bolshevism

1. For my next trick in the arena of niche overthinking-it monographs, I am going to be writing a book on the Rebecca riots. There have already been magisterial studies of the movement which have focused on its political and economic aspects, but I am going to look at its social and cultural aspects, and the ways in which it had more variety, more politics, and more of Old Weird Wales than is generally acknowledged.

To include: why there was a bit more to the movement than hill-farmers smashing up tollgates in bonnets, petticoats and false beards; the nature of Welsh resistance to early industrial capitalism (as touched on in this post); contemporary ideas of gender and the early Victorian undermining of female social and sexual agency; how Rebecca’s image became a national ‘idiom of defiance’ – basically, a meme – and wider issues hopefully relevant to today, eg “rough” versus “respectable” protest; the traditions of masked and anonymous protesting; and how popular culture can be integrated into popular resistance.

Don’t worry, I’m fully aware that this book will be of interest to about four people at a push.

*

2. The last time I was in the House of Commons in any official capacity, I was taking students to lobby against the introduction of top-up fees. Our side having narrowly lost that vote, I then got massively drunk in the ULU bar, decided to give up student politics as a mug’s game, ranted at a Sky News crew and eventually had to be carried out to a taxi by members of my delegation.

Last month I attempted to conduct myself with greater dignity, and spoke on this Zero Books panel. Strike! magazine wrote up the evening here.

Things I’ve written elsewhere:

- For the Wales Arts Review, What Riot Grrrl Did and Didn’t Do For Me: on female artistic expression, theory vs practice, post-punk, class and feminism, the 90s, adolescence, and Courtney Love, I think that’s everything.

- For Planet on the centenary of the Senghenydd colliery disaster, a piece about the issues it continues to raise around Welsh identity and the history of working-class exploitation and resistance.

The Manics’ Next Step

We cannot get rid of employers and slave-driving in the mining industry, until all other industries have organized for, and progressed towards the same objective. Their rate of progress conditions ours, all we can do is set an example and the pace.

– The Miners’ Next Step (1912)

Nicky Wire in the Quietus reviews (previews?) Rewind The Film.

Of course, having put away excitement and belief and other childish things, I no longer await a new Manic Street Preachers album with the same starry-eyed avidity I once did. (Do you?)

On the title track and its accompanying video, I liked what Lost Communication had to say:

… and I’d add only that the swampland that lies between mawkishness and sentimentality is a thoroughly Welsh place to get stuck. On at least one of the tracks discussed in the Quietus interview, though, ‘30 Year War’, the band seem to succeed in side-stepping the rose-tinted ‘noble decline’ trap:

“It’s not about Thatcher, it’s definitely about Thatcherism, about the establishment across the last 30 years, and it doesn’t matter what government is around, we always love to portray ourselves as this holier than thou country, and yet we have scandal after scandal uncovered, right to the root of power, government, Murdoch, the police, Hillsborough, this stupification of the class I grew up in, which I think all stems from Thatcherism really. The idea that if you break down any power that we had we’re going to be fucked forever…

I find that elitist, ‘We know what’s better’ is so all pervading, from the monarchy to fucking Cameron to Mumford and Sons. We’re just told… what did one of Mumford and Sons say the other day? ‘Either ignore it or celebrate it.’ What a fucking futile attitude. Don’t say anything bad, just ignore it or celebrate it. So what about fascism then? We don’t like it, we’ll just ignore it. It does feel like the last five years has been such a redress of monarchy and establishment and public school through all points of our culture. I feel a bit helpless about it.”

Bang on, of course, as is everyone else who appears to be waking up and wondering what went wrong after the Old Weird Nineties (that Mumfordian ‘ignore or celebrate’ ultimatum is straight outta Cool Britannia, although much of that era was more notable for its ability to do both at once).

I’m glad that bullish bullshit detector of his endures to an extent. It’s encouraging that the disingenuous and damaging nature of both austerity and austerity chic is being increasingly noted, but the lack of analysis and alternatives are still too glaring for this to be any more deeply gratifying. Not that analysis or alternatives have ever been the preserve or the responsibility of rock stars.

Beneath the paving stone, the plug.

Welsh edition:

1. I wrote this piece for the Wales Arts Review on Welsh history, politics and identity. Yes, again.

2. In the next issue of Planet: the Welsh Internationalist, I have written on the relationship between Welsh artists and London in the very poor disguise of an album review.

3. If you’re at this year’s Green Man, I will be there to speak to ex-Kenickie members Emma Jackson and Marie Nixon on music, gender, class, the 90s, you know the drill. My life as outtake from Phonogram continues. I shall endeavour not to use the term “escapist proletarian-glam aesthetic” more than once but can’t promise anything.

Plus:

I wrote this for the summer issue of Strike! on why hipsters, shit as they and their gentrifying camp-followers may be, are nevertheless more symptom than cause.

Seizing the Dydd.

The Wales Arts Review takes an interesting and optimistic shot at galvanizing the cultural future of the country. I found it sobering to contrast this overview, which looks forward from within, with the hellishly depressing one contained in another recent article called ‘The unbearable sadness of the Welsh valleys’. This does exactly what it says on the tin: an external observer tracks the Valleys’ economic decline, and its social and cultural impact, in what sometimes reads like a negative version of the Victorian travelogues which eulogised the beauties of the Welsh landscape (and largely overlooked their quaint but inconvenient inhabitants).

Without wishing to damn with faint praise, I’ll take that second article over MTV’s The Valleys, although its paternalist hand-wringing and lack of solutions make about as much constructive contribution. As I concluded after my own incoherent trawl through my fatherland’s history and identity, focusing on an oversimplified, often romanticised past, however grievous and traumatic its loss, produces only stasis and resentment. We need to move past this, even at the risk of losing what little identity we have (and it’s currently an overwhelmingly negative one, at best pitiful and at worst exploitative and sensationalist). This needn’t automatically mean considering oneself part of, as the Wales Arts Review‘s very good article has it, ‘a generation unscarred by the battles of the past’ – any product of the south Welsh coalfield, as of other parts of post-industrial Britain, is thoroughly scarred by the battles of the past and knows themselves to be. But it does mean that these scars needn’t be one’s defining feature, in one’s own view or that of outside observers.

The problem is, of course, that it’s one thing to move forward in terms of arts and culture, but socio-economically speaking it’s quite another.

Elsewhere.

Little Empires V: Coming Up For Air

This is the fifth AND LAST in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Three: Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes

Part Four: Everybody Hates a Tourist

Part Five

“For a start, the very fact that we were Welsh meant that we had to try 100 times harder than any other group. Even now, in some terrible news magazine, someone’s reviewed the album and the headline is ‘Boyos To Men’. And I’m not saying it’s racist or anything: I just find it incredibly thick. In a way I’m glad I’ve got all that now: it gives me something to rail against, to use as a creative feeder.”

Can you speak any Welsh?

“We were never allowed to learn. And that’s another big bit of resentment in us: it wasn’t on the curriculum for the whole of South Wales. I’d have loved to have been able to speak Welsh.”

“Damn it all, you can’t have the crown of thorns and the thirty pieces of silver.”

– Aneurin Bevan, c. 1956

After all this, I mean, I still feel Welsh, and I still call myself it. ‘Welsh’ for me can be a residual, reserve identity, buried or submerged, but still enduring; something to cling to when adrift, rightly or wrongly; something to anchor me. What the identity consists of, though, I’ve never been sure. It’s not a national identity but a local one, and its localness – the ways in which I feel myself to be Welsh -always keeps me conscious of the ways in which I’m not. Rather than ‘yes, that’s it’, it’s easier to say ‘yes, but that’s not all it is’. Wire in that 1997 interview may well proclaim himself ‘into oneness’, but there is no One Wales. Even beyond the country’s linguistic, geographic and political divisions, there exist multiple fractured identities, defining themselves by the local not the national – particularly through being from X, rather than from Cardiff. Growing up, attributes, accents and attitudes were associated with specific areas, towns, areas of towns, sometimes pinned down to exact streets. The Wales of swords and stone circles, drowned lands, dragons and druids, Taliesin and Eisteddfodau exists in romance alongside the reality of GLC’s Newport, Gavin & Stacey’s and Simon Price’s Barry Island, the drug-soaked, politically corrupt underworld of Lloyd Robson’s Cardiff Cut, the Valleys anti-romances of Rachel Trezise, and a multitude of other identities scattered and self-contained but highly secure in their specifics. To brush under the national carpet all of these peculiarities, to smother them in fantasies of ancient racial purity, the flag, the Senedd, or MTV’s predictably execrable The Valleys, does justice to nothing Continue reading

Little Empires IV: Everybody Hates a Tourist

This is the fourth in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’. Stay tuned with suitably low expectations.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Three: Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes

Part Four

To be Welsh is to be conscious

At dusk of the spilled blood

That went into the making of the wild sky…

And an impotent people,

Sick with inbreeding,

Worrying the carcass of an old song.

– ‘Welsh Landscape’, R S Thomas

To be born Welsh is to be born privileged

Not with a silver spoon in your mouth

But music in your blood and poetry in your soul

– from ‘In Passing’, Brian Harris

While living in London I had that second quote on a keyring for several years; if you’re Welsh, you might have done so too – or you might have had it on a mug, a teatowel, an embroidered sampler. The 1967 poem from which it is (mis)taken contains far bleaker Thomas-esque currents (‘ugliness that scars the spirit / as the earth’, ‘rivers of mingled blood and sweat’), but this opening snippet has become both tourist branding, found everywhere it can be sold, and a kind of faux-folk fetish for the Welsh themselves. With its elevation of ‘natural’ cultural creativity over material advantage making a virtue of necessity, it is our Keep Calm and Carry On – a comforter, a pacifier. Continue reading

Little Empires III: Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes

This is the third in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’. Stay tuned with suitably low expectations.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Three

The furies are at home

in the mirror; it is their address.

Even the clearest water,

if deep enough can drown.

Never think to surprise them.

Your face approaching ever

so friendly is the white flag

they ignore. There is no truce

with the furies. A mirror’s temperature

is always at zero. Its camera

is an X-ray. It is a chalice

held out to you in

silent communion, where gaspingly

you partake of a shifting

identity never your own.

– ‘Reflections’, R S Thomas

Most people see me as a rake, womanizer, boozer and purchaser of large baubles. I`m all those things depending on the prism and the light. But mostly I’m a reader.

– Richard Burton

Besides the drowning of Tryweryn, Ready for Drowning also snags the idea of drowning one’s sorrows, referencing the alleged propensity of the Welsh for – what shall we call it? – a steady, a committed, a co-dependent relationship with drink. The association of Wales with a certain kind of romanticised and spectacular inclination to alcoholism – not so much in reality as in legend – still persists. Ready for Drowning compares the flooding of Tryweryn with how, according to Wire: ‘a ceaseless chain of Welsh people seek to adjust to their circumstances by drowning their synapses in alcohol. …‘it’s half Richey, half Welsh identity – about how many of our icons either drink themselves to death or run away’. Continue reading

Little Empires II: Fear Death By Water

This is the second in an overlong and overthinking-it series of posts on Wales, history, identity and the Manic Street Preachers, as filtered through the song ‘Ready for Drowning’. Stay tuned with suitably low expectations.

Part One: All Surface No Feeling

Part Two

In the Bible, God made it rain for 40 days and 40 nights. That’s a pretty good summer for Wales. That’s a hosepipe ban waiting to happen… I was eight before I realised you could take a cagoule off.

– Rhod Gilbert

O where are our fathers, O brothers of mine?

By the graves of their fathers, awaiting a sign…

The slopes of slag and cinder

Are sulking in the rain

And in derelict valleys

The hope of youth is slain.

– from Gwalia Deserta, Idris Davies (1938)

Idris Davies, the coalfield’s ‘bitter dreamer’, lost a finger in a mining accident and was first radicalised and then disaffected by his participation in the 1926 General Strike. Subsequently unemployed, and having been introduced to the work of Shelley by a fellow miner, he began four years of what he called ‘the long and lonely self-tuition game’. In his poetry, as fanboyed by T S Eliot, he is notably attached to the word ‘derelict’, especially as a description of the south Welsh valleys, desolate and desecrated by industry. (They’ve only grown more apt as a pairing.) Davies has little of R S Thomas’ brutally bleak, at-bay snarling; his jeremiads are, like the landscape and land he describes, just ‘sulking in the rain’, sad and sullenly resigned. Continue reading

Little Empires: on Wales, history, identity, and the Manic Street Preachers

‘I’ve never written about Welsh identity before: these days, I’ve got to search for things to write about, whereas in the past everything would be driven by anger and all the rest of it. Now I’ve got to delve more… Ready For Drowning is the most complete song I’ve ever written, I think…’

One: All Surface No Feeling

Tree stumps exposed by low water levels of the Llyn Celyn reservoir. Its construction in the early 1960s involved the flooding of the Tryweryn valley and the drowning of the village of Capel Celyn.

“The submerged land of Cardigan Bay is called Cantre’r Gwaelod (‘the lowland hundred’). It was defended from the sea by an embankment and sluices. Seithennin was keeper of the sluices, and one evening when there was a great banquet he became drunk and left the sluices open. The water rushed in and drowned the inhabitants. The poet Taliesin was the only one to escape alive.

“When man first came to live on the coast of Wales (sometime between the Neolithic and the Iron Age), the sea level was still rising between Wales and Ireland, separating the two countries further and further, and the legend relating to the drowning of the Lowland Hundred probably developed as a result of folk-memory of a sudden coastal flooding many centuries ago. The remains of peat and tree trunks which are visible on the beaches when the tide is far out further captured man’s imagination. Similar traditions are connected with certain Welsh lakes [and] with other parts of the Welsh coast… The moralistic and onomastic elements in all these traditions are very obvious.”

– Robyn Gwyndaf, Welsh Folk Tales (1989)

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish?

– from The Wasteland, T S Eliot (1922)

Lately I’ve been revisiting both the land of my birth and upbringing and mid-period Manic Street Preachers. The latter was a moderately painful process which has, incidentally, left me staggered all over again that ‘Tomorrow Steve Ovett has injured his calf’ was considered to pass muster as a lyric. I don’t generally subscribe to the idea that everything good about the band vanished along with Richey; I think Design for Life is, while maybe not the best thing they’ve accomplished, at least the most valedictory, the thing I remain most proud of them for doing. But yeah, they should perhaps have called a halt to things shortly after that. Continue reading

Radical history: the Scotch Cattle rebranded

In my former life as a shiftless, rootless, and economically useless humanities student, I researched and wrote on weird, failed, disreputable and consequently marginalised or forgotten moments in the history of popular resistance to industrial capitalism – food riots, rough music, cross-dressing and animal masks, legendary figureheads (Ludd, Swing, Rebecca) and the use of theatre, symbol and spectacle. My guiding principle was that eighteenth and nineteenth-century protest often contained a popular symbolic and ritual repertoire adapted for the purposes of expressing discontent, and that it also made visible an increasing conflict between established popular custom and the nascent doctrines of industrial capitalism and constitutional law. Some of what I wrote is here, though it’s not very good.

If you’ve never read about any of this then you ought, it’s great. E P Thompson’s concept of a ‘moral economy’ motivating collective social and economic protest – the idea of a continuous extra-parliamentary and extra-legal tradition based on an appeal to established popular rights, which juxtaposed natural and social justice with prevailing civil and criminal laws – still finds expression where it has to, from ‘proletarian shopping’ to the ideas of social justice expressed through ‘rough music’ in the recent kickings-off in Montreal and Quebec. I mean, one might be tempted to conclude that the increasingly visible powerlessness of the average citizen to exercise opinion by constitutional means has encouraged a return to more immediate and hands-on methods of collective bargaining.

Anyway, the Scotch Cattle – an early attempt at industrial organisation in 1820-40s south Wales – are obscure and getting obscurer: one monograph, a couple of local history articles, and minor mentions here and there, usually with audible disapproval. The Scotch Cattle tend to be dismissed in traditional histories of labour and of Wales, due to their failure to fit neatly into narratives of either the sober and respectable growth of trade unionism or the development of an orderly Welsh society. This is a large part of what interests me about them and others like them, though they are also fascinating on their own terms, being at once an obvious and logical response to the conditions of early industrial capitalism, and peculiar as fuck.

Much to my own surprise, I have an article on the Scotch Cattle published in this month’s Welsh History Review – I presume out now, or impending. My take on them is that they are a hybrid movement, representing the attempts by workers to transfer their accustomed techniques of pre-industrial protest – yer basic charivari – to the untested environment of the south Welsh coalfield in its wild and brutalising stage of development (in Gwyn A. Williams’ useful phrase, its ‘frontier years’). Divorced from their original context and the social relations on which they depended, these techniques were open to mutation and fragmentation, and their effective operation was no longer guaranteed, with less than hilarious consequences.

That’s what my research has led me to conclude, at least. Throw in proto-class war, contested constructions of masculinity, and the old ritualised ultraviolence, and you’ll be unsurprised to learn that my application for AHRC funding got turned down three years on the trot.

Shameless, 1974

The forward march of labour halted.

Two things I wrote recently on the music, culture and politics of that weird, desultory decade, the 1990s:

1. Up Close and Personal: Lost Girls

For the decade blogs, my Tesco Value Greil Marcus number on gender, class, Britpop and everything after, chav-hysteria and narrowing of access.

2. Rebel Music #5: Manic Street Preachers

For New Left Project, a cleaned-up and condensed version of my customary closing-time rant on the politics of the Manic Street Preachers. I know I fail to mention, eg, Soviet chic, or Castro, or self-harm and anorexia, or the band’s appeal to teenage girls, or anything after This is my Truth Tell me Yours. It’s not that they’re irrelevant, they’re just relevant to a different article. Or possibly a whole book.

Privatize everything > Occupy the tollgates.

You’re all joking about the roads being next for privatization, aren’t you. Aren’t you. Oh, you’re not.

It’s just that in another lifetime, one of toil and blood, I did my whole thesis about a little local difficulty which centred around privatized road networks: the ridiculous/amazing “Rebecca riots”.

Part of what I liked about the study of history was that it did occasionally seem – by no means always, of course – as though society in general wasn’t too disparate, atomized, hopelessly confused, thick, or arrogant to learn from its mistakes.

For example: ‘Wow, at least private roads wouldn’t be an option /these days/’, I’d often muse, back in the day, having conducted hours of research and written thousands of words about how badly it had all worked out in the face of popular insistence upon public utilities being kept for the collective good rather than left to the profiteering of incompetent private companies.

(The Rebecca riots were a lot more complex than that, obviously, hence my studying them in the first place, and my bringing in their use of masking, cross-dressing, ritually smashing stuff, inter-class cooperation, liminal states, gender essentialism, and the disparity between lived experience and political and media discourse – don’t worry, neither the Taxpayer nor Hard-Working Families were paying for me to study any of this – but the general resentment of private ownership as leading to general neglect and profiteering holds true as a contributing factor – as indeed it holds true over two hundred years on.)

I’m sick of saying we’re being taken back to the Victorian age, but this? Is the government just trolling, now?

Or, with less (or perhaps more) conspiracist fervour: RT @bengoldacre Wouldn’t it be a shame if this distant roads nonsense distracted you from the Lords’ final vote on #NHSbill.

The Pits and the Pendulum

I’ve had coalmining on my mind recently. Contra last week’s Metro, I don’t think it’s accurate to say ‘the world looked on in despair’ at events at Gleision Colliery – in fact the story was predictably underreported and largely unremarked upon by my usual social media circle, until the story became a self-evidently human tragedy, whereupon it was hardly engaged with at any deeper level than that. Anyway:

As the admittedly lame title of this blog suggests, the coalmine for me is bound up with a certain sense of national identification, but also, if not more so, with class and regional associations. I feel that I have more in common with someone of my age from a post-industrial area in (say) south Yorkshire, than I might with someone from rural west or north Wales or indeed the great bright-lit sprawl that is Cardiff and the Vale. Weighted against this potentially mawkish shoulder-to-shouldering with other unemployment blackspots is the knowledge that this landscape as a functioning entity, as something that defined one as part of and in relation to a certain workforce, as the sum of one’s labour, has (been) altered out of all recognition and what it tends to be seen as generating now is dysfunction. But the mine as a symbol of shared frames of reference carries an inescapable emotional weight. Continue reading

Libraries Gave Us Power: notes on the Manic Street Preachers and class

So I liked Owen Hatherley’s piece on Pulp, and I knew reading the comments would spoil it all, but reader, I read them. The majority were bafflingly wet-blanket in nature, wildly and wilfully missing the article’s point, if studded with bits of valid and interesting discussion. Specifically, though, I was surprised to encounter in both the article and the responses a lack of any mention of Manic Street Preachers. Surely you can’t reach back into the 90s, grasping for lines to describe the sociopolitical here and now, without burning your fingers on the white-hot irony of ‘A Design for Life’?

‘We don’t talk about love,

We only want to get drunk

And we are not allowed to spend

As we are told that this is the end’

If Pulp were the last art-school band (and I’m by no means convinced of that), then surely the Manics were the last artistic gasp of a certain breed of late 20th-century industrial working class? Continue reading

All Quiet on the First Great Western Front

Last week I returned to the Old Country – well, not the Old Country itself, but rather Cardiff, my land’s increasingly swish and cosmopolitan capital, with its rapaciously expanding shopping-and-eating quarter and its incongruous postmodern street sculptures making it feel a bit like a Torchwood theme park. The second most immediately notable thing about Cardiff at the minute is the preponderance of Emo kids there. I know Emo hit the subculturally-attuned youth of south Wales hard, but that was some years previously, and I was aghast to discover that the wretched thing still holds much of the city in its terrible, slappable, Lego-fringed grip. Will we never be set free?

This weekend I’m going to Southampton to be a superstar DJ. By which I mean, to hand over some mix CDs and hope for the best. I hope you all have good weekends; here are some curios to take you into it. Continue reading