Tagged: beneath the paving slab the plug

Some forthcoming events I’m doing

Variously on music, politics and history – please come along if you’re interested.

Saturday 19th May: @CultishEvents playback of The Holy Bible at which I’ll be giving an introduction to the album and Triptych. Details: https://www.facebook.com/events/1503877846345865/

Saturday 2nd June: talking about music and misogyny in Under My Thumb: Songs That Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them, with the book’s co-editor Eli Davies and our contributors Frances Morgan and Anna Fielding. Details: http://stokenewingtonliteraryfestival.com/snlf_events/under-my-thumb/

Saturday 9th June: I’ll be explaining the early Victorian primitive rebellion known as the Rebecca riots as part of Chartism Day. Details: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/history/history-events-publication/chartism-day

Under My Thumb: Songs That Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them

Under My Thumb is a collection of women’s music writing, edited by Eli Davies and me, in which contributors discuss being fans of politically dubious music, artists and songs. It’s out in October from Repeater Books and available to pre-order now.

Artists covered, in-depth or in passing, include: Dion and the Belmonts, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, Carole King, The Crystals, Phil Spector, Bob Dylan, Pulp, Gary Puckett & the Union Gap, Anni-Frid Lyngstad, The Rolling Stones, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, David Bowie, Pure Prairie League, Rod Stewart and The Faces, Eddie Cochran, AC/DC, Van Halen, Guns ‘N’ Roses, L7, Elvis Costello, murder ballads, Nick Cave, Sir Mix-a-Lot, Run the Jewels, 2Pac, Eminem, Weezer, The Divine Comedy, Jarvis Cocker, Combichrist, Jay-Z, The Libertines, My Chemical Romance, Fall Out Boy, Kanye West, The-Dream, Swans, Taylor Swift.

Full list of contributors: Amanda Barokh, K. E. Carver, Marissa Chen, Zahra Dalilah, Eli Davies, Judith May Fathallah, Anna Fielding, Alison L. Fraser, Laura Friesen, Beatrice M. Hogg, Rhian E. Jones, Jacey Lamerton, Abi Millar, Emily McQuade, Frances Morgan, Christina Newland, Elizabeth Newton, Stephanie Phillips, Nina Power, Charlotte Lydia Riley, Kelly Robinson, Jude Rogers, Jasmine Hazel Shadrack, Em Smith, Johanna Spiers, Manon Steiner, Fiona Sturges, Rachel Trezise, Larissa Wodtke.

Out now: Triptych, Three Studies of Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible

Triptych: Three Studies of Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible is my next book, co-written with Daniel Lukes and Larissa Wodtke, coming out in February next year from Repeater Books.

My bit looks at the politics and pop culture of 90s Britain, growing up in post-industrial Wales, class and gender and the rest of my usual stuff, and how the album fit or didn’t fit into that context.

(Obviously a cultural materialist analysis of the Manics’ least commercial album is the one thing the world needs right now.)

A request to Manics fans out there

This year I’ll be writing a book on Manics album The Holy Bible, along with Larissa Wodtke and Daniel Lukes. My section will focus on the album’s social and political context ie Britain in the 90s, the album’s appeal to teenagers, and reasons why the band had such a huge female fanbase.

As part of researching this book, I’d find it helpful to speak to other fans of the band about the album – both those who, like myself, grew up with the Manics in the 90s, and those who discovered them later. (If you’re interested in what I’ve written previously on the band, most of it is here.)

If you’d be willing to tell me a bit about your experience as a Manics fan, please reply to this post with a contact email or, if you prefer, contact me yourself on theholybibletriptych@gmail.com. Thank you!

In advance of the Manics’ anniversary tour of The Holy Bible, the Cardiff production company Barefoot Rascals is making a short documentary on the album’s history and its impact on fans, involving interviews with Simon Price, myself and others. To get the film produced, we are asking for funding on Kickstarter – please donate a couple of quid here if you can. We are halfway to meeting the funding target so far.

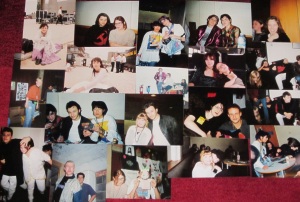

Below is a guest post and pictures by former music photographer Lorna Cort, who remembers the original album tour in 1994 and whose pictures will be used in the documentary.

The Manic Street Preachers were my life. After discovering Stay Beautiful in the Summer of 1991 I’d followed tours, collected just about everything, written too many letters to James, learned to play guitar ( a white Gibson Les Paul obviously!) and helped form the band of fellow Manics fans ‘Dead End Dolls’.

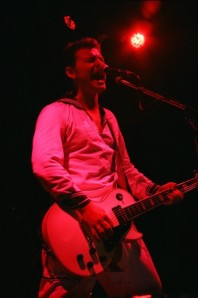

By 1994, I bought a camera and decided I was going to be a music photographer. I can’t remember who gave me a photo pass for Portsmouth Guildhall on 12th October but thank you, I have treasured the results. Back in the olden days of film and developing at Boots, I had no idea how the photos would turn out. As well as manual focus I had to contend with stage divers flying overhead, security guards taking up all the room in the photo pit, and the deafening sound of a thousand screaming fans 2 feet behind me and the flimsy barrier! The gig was over in a flash, I remember James raised his eyebrows ‘hello’ at me, the white sailor suit looked amazing under the lights, the sound was incredible, I wanted to sing along but no, I was a photographer… I couldn’t look like I was actually enjoying myself!

The Holy Bible was a challenge to listen to, it was at times uncomfortable, shocking, it was emotional… and it was perfect. When I look at my photos 20 years later I see the concentration on James’ face, the determination to get all the words out, Nick’s anonymity, head down with a nose-skimming fringe, and I see how painfully skinny Richey’s arms look, and that he has the word ‘LOVE’ written in black marker on his fingers. They were so beautiful, so focused.

I wanted to be part of The Holy Bible – My Testament to share my photos with old fans and new, to celebrate one of the most amazing records ever created and to remember the excitement and love I had for this band. To paraphrase Nick – they remain the most intelligent people I ever met in my life. I so hope this project goes ahead and maybe brings the Holy Bible to new listeners. Thank you.

Updates and links of mine, past and future.

– Recently I wrote a short review of the film Pride.

– I also wrote a long review of Agata Pyzik’s book Poor But Sexy. NB As a child of the nineteen-eighties, way before online discussions on how to be a fan of problematic things, I remember being starry-eyed about the Soviet Union = how I do confessional journalism.

– In Cardiff this Saturday, I’m doing a talk with, among others, Craig Austin, the author of this excellent article on the decline and fall of political pop. Get your tickets free at this link.

– And on Thursday 6th November I’m speaking in Manchester on “Poverty Porn and the Welfare State”, on the impact of media portrayals of poverty on government policy and public attitudes towards welfare. More info and event programme here.

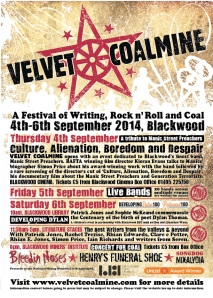

Velvet Coalmine, the festival: in Blackwood, 4-6 September

The first Velvet Coalmine Festival, featuring the best of Valleys music, art and literature, will be happening next weekend. Like Camden Crawl, but with more coal.

Among loads of other acts, I will be talking to the excellent Rachel Tresize about the ins and outs of having been a female Manics fan.

“Velvet Coalmine aims to create a platform for music, writing and ideas in the Blackwood area that allows our voice to be heard and celebrated. It allows our stories to be told and communicated to the wider world without censorship and our cultural heritage and identity to be expressed on its own terms without interference, without suppression and without agenda. The history of the Valleys is littered with exploitation, neglect and indifference but has proved a birthplace to a myriad of thinkers and pursuers of social justice and in an era when Old Etonian privilege continues to shape and influence decision-making and politics in the UK, creating an arts festival influenced by the radicalism of the 1984-85 miner’s strike and the Centenary of the Senghenydd mining disaster feels both timely and appropriate.”

Full listings and contact details can be found here on the website. Come on down.

On talking about pop when you want to talk politics.

Alex Niven’s book on Oasis’ Definitely Maybe is out now and worth your time. It’s a book about working-class art, working-class politics, and the decline of both in Britain since the 90s, but there’s no denying the fact that it’s also a book about Oasis. So for the purposes of this post, which isn’t about Oasis, let’s talk about Oasis first:

Yes, it’s alright if you think Oasis were shit. Yes, Oasis went downhill fast – almost immediately, in fact. Yes, Oasis were a more ‘authentic’ version of the freewheeling should-know-better casually chauvinist Lad that, in Niven’s term, the ‘bourgeois wing of Britpop’ attempted to pantomimically portray, and no, this wasn’t necessarily a good thing. Music press, tabloids and lad-mags in the 90s lionised the Gallaghers’ laddishness as part of a tediously retrograde cultural discourse that was intent on rolling back the ‘politically correct’ gains of the decades before. This same discourse imposed a false dichotomy of class, in which Oasis’ supposed proley authenticity was linked with loutish ignorance and excess, while experimentation, education and glorious pretentiousness were presented as the preserve of the middle class. So yes, Oasis were damaging. But more by accident – or by deliberate exploitation by a largely middle-class cultural industry – than by design.

And yes, there was more than Oasis happening in the 90s. The issue here is that no other band got so big, so phenomenally quickly, and the question is whether anything interesting can be said to explain that – you know, beyond the not-even-trying paradigm of “people like Coldplay and voted for the Nazis; you can’t trust people, Jeremy”. The book’s background argument on this, to which I am a rock-solid subscriber, is that, as 90s politics capitulated to a post-Thatcher consensus, a more subversive, anti-establishment spirit persisted in early-90s pop culture – including early Oasis alongside the Manics, Pulp, Kenickie etc – which then got flattened under Cool Britannia, Blairism, and Britpop’s imperial stage. Overthinking it? Yeah, if you like. Better than underthinking it, mate. Continue reading

Bonnets and Bolshevism

1. For my next trick in the arena of niche overthinking-it monographs, I am going to be writing a book on the Rebecca riots. There have already been magisterial studies of the movement which have focused on its political and economic aspects, but I am going to look at its social and cultural aspects, and the ways in which it had more variety, more politics, and more of Old Weird Wales than is generally acknowledged.

To include: why there was a bit more to the movement than hill-farmers smashing up tollgates in bonnets, petticoats and false beards; the nature of Welsh resistance to early industrial capitalism (as touched on in this post); contemporary ideas of gender and the early Victorian undermining of female social and sexual agency; how Rebecca’s image became a national ‘idiom of defiance’ – basically, a meme – and wider issues hopefully relevant to today, eg “rough” versus “respectable” protest; the traditions of masked and anonymous protesting; and how popular culture can be integrated into popular resistance.

Don’t worry, I’m fully aware that this book will be of interest to about four people at a push.

*

2. The last time I was in the House of Commons in any official capacity, I was taking students to lobby against the introduction of top-up fees. Our side having narrowly lost that vote, I then got massively drunk in the ULU bar, decided to give up student politics as a mug’s game, ranted at a Sky News crew and eventually had to be carried out to a taxi by members of my delegation.

Last month I attempted to conduct myself with greater dignity, and spoke on this Zero Books panel. Strike! magazine wrote up the evening here.

Things I’ve written elsewhere:

- For the Wales Arts Review, What Riot Grrrl Did and Didn’t Do For Me: on female artistic expression, theory vs practice, post-punk, class and feminism, the 90s, adolescence, and Courtney Love, I think that’s everything.

- For Planet on the centenary of the Senghenydd colliery disaster, a piece about the issues it continues to raise around Welsh identity and the history of working-class exploitation and resistance.

“My father still reads the dictionary every day. He says your life depends on your power to master words.”

Obviously I’m pleased, not to mention surprised, to see my book reviewed in a national newspaper that isn’t the Morning Star. Without wishing to sound ungracious, though, it is mildly exasperating to see the review uncritically reflect the idea that using Big Words makes the writing ‘over-done’ and ‘in thrall to the strangulated cult-studs vernacular’. I do know what John Harris means by the latter term, of course, and I will write at a later point about the regrettable tension that seems to occur in a lot of contemporary writers, invariably ones on the left, between the wish to make one’s writing easily understood and the fear of sounding overly simplistic. The latter, incidentally, often seems to be fuelled by a feeling that, in order to be taken seriously by a small potential readership whom one has been conditioned to regard as cultural and academic gatekeepers, one needs to somehow ‘prove oneself’ by larding one’s prose with gobbets of Žižekian sophistry, lest one stand accused of being low-brow or naïve or Owen Jones or something.

The thing is that these words don’t strike me as ‘big words’ when I’m thinking or writing them, they simply strike me as the most appropriate words to use. I also dislike repeating words, and so I use a lot of words which mean similar things but which I guess might grow progressively more outlandish until the book ends up describing 90s popular culture as ‘atavistic’ rather than simply ‘backwards-looking’. Sorry about that, I guess? Ironically enough though, the review goes on to cite ‘those great pop-cultural intellectuals’ the Manic Street Preachers, whose lyrics were nothing if not a strangulated vernacular of their own. For good or ill, the Manics, in their encouragement of reading and general cultural immersion as a cure for small-town boredom and alienation, were far more of an influence on my subsequent vocabulary than some nebulous villain called Cult-Studs.

So here’s a question. Is vocabulary now considered a class signifier? Does understanding, and using, ‘big words’, mark you out as someone who cannot belong to ‘the ordinary’, ‘the normal’, the demographic conveniently delineated by external commentators as ‘working class’? Or is it the case that one’s socio-economic background does not preclude one having an expansive vocabulary? Might one have gained a knowledge of ‘big words’ from, uh god I don’t know, reading books and reading broadsheets, despite where one was brought up? And does knowing ‘big words’ mean you can never be categorised as ‘working class’? Continue reading

Elsewhere.

Post-punk: a plug and a playlist.

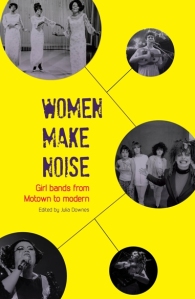

I am in print this month, having written a chapter on women in post-punk for Julia Downes’ new history of the girl band, Women Make Noise. A surprisingly difficult part of this was establishing what we talk about when we talk about post-punk. Post-punk’s disorderly, subversive and category-resistant nature has seen it marginalised in accounts of its era, although the past few years have produced a handful of useful retrospectives, as well as the early-2000s revival of post-punk musical techniques which, if you still can’t explain what it is, at least make it easier to explain what it sounds like.

For me, a large part of post-punk’s significance was that it seemed to involve an unprecedented amount of women as artists, fans, critics and ideologues. Extending the gains of punk’s emphasis on DIY culture, accessibility and amateurism, post-punk women were able to take their bands in experimental and innovative directions. Post-punk’s ideological concern with the politicisation of the personal, and with identifying and promoting authenticity in the face of popular cultural stereotypes, lent itself to exploration from a feminine and feminist angle, resulting in lyrics which demystified and deconstructed conventional femininity, love, sex and romance, and which analysed social and cultural pressures on women or the tensions of personal relationships in implicitly political ways. Continue reading

Radical history: the Scotch Cattle rebranded

In my former life as a shiftless, rootless, and economically useless humanities student, I researched and wrote on weird, failed, disreputable and consequently marginalised or forgotten moments in the history of popular resistance to industrial capitalism – food riots, rough music, cross-dressing and animal masks, legendary figureheads (Ludd, Swing, Rebecca) and the use of theatre, symbol and spectacle. My guiding principle was that eighteenth and nineteenth-century protest often contained a popular symbolic and ritual repertoire adapted for the purposes of expressing discontent, and that it also made visible an increasing conflict between established popular custom and the nascent doctrines of industrial capitalism and constitutional law. Some of what I wrote is here, though it’s not very good.

If you’ve never read about any of this then you ought, it’s great. E P Thompson’s concept of a ‘moral economy’ motivating collective social and economic protest – the idea of a continuous extra-parliamentary and extra-legal tradition based on an appeal to established popular rights, which juxtaposed natural and social justice with prevailing civil and criminal laws – still finds expression where it has to, from ‘proletarian shopping’ to the ideas of social justice expressed through ‘rough music’ in the recent kickings-off in Montreal and Quebec. I mean, one might be tempted to conclude that the increasingly visible powerlessness of the average citizen to exercise opinion by constitutional means has encouraged a return to more immediate and hands-on methods of collective bargaining.

Anyway, the Scotch Cattle – an early attempt at industrial organisation in 1820-40s south Wales – are obscure and getting obscurer: one monograph, a couple of local history articles, and minor mentions here and there, usually with audible disapproval. The Scotch Cattle tend to be dismissed in traditional histories of labour and of Wales, due to their failure to fit neatly into narratives of either the sober and respectable growth of trade unionism or the development of an orderly Welsh society. This is a large part of what interests me about them and others like them, though they are also fascinating on their own terms, being at once an obvious and logical response to the conditions of early industrial capitalism, and peculiar as fuck.

Much to my own surprise, I have an article on the Scotch Cattle published in this month’s Welsh History Review – I presume out now, or impending. My take on them is that they are a hybrid movement, representing the attempts by workers to transfer their accustomed techniques of pre-industrial protest – yer basic charivari – to the untested environment of the south Welsh coalfield in its wild and brutalising stage of development (in Gwyn A. Williams’ useful phrase, its ‘frontier years’). Divorced from their original context and the social relations on which they depended, these techniques were open to mutation and fragmentation, and their effective operation was no longer guaranteed, with less than hilarious consequences.

That’s what my research has led me to conclude, at least. Throw in proto-class war, contested constructions of masculinity, and the old ritualised ultraviolence, and you’ll be unsurprised to learn that my application for AHRC funding got turned down three years on the trot.

The forward march of labour halted.

Two things I wrote recently on the music, culture and politics of that weird, desultory decade, the 1990s:

1. Up Close and Personal: Lost Girls

For the decade blogs, my Tesco Value Greil Marcus number on gender, class, Britpop and everything after, chav-hysteria and narrowing of access.

2. Rebel Music #5: Manic Street Preachers

For New Left Project, a cleaned-up and condensed version of my customary closing-time rant on the politics of the Manic Street Preachers. I know I fail to mention, eg, Soviet chic, or Castro, or self-harm and anorexia, or the band’s appeal to teenage girls, or anything after This is my Truth Tell me Yours. It’s not that they’re irrelevant, they’re just relevant to a different article. Or possibly a whole book.

A quick request (re. images of women in post-punk).

So: I’ve written a chapter on female post-punk musicians* for a forthcoming women-in-music book. I mostly talk about the Slits, the Raincoats, Linder Sterling, Lydia Lunch (unavoidably), ESG, the Au Pairs, Delta 5, Pauline Black, Barbara Ess, Ut., Mars, the Bush Tetras, the Bloods, Malaria!, Kleenex/LiLiPUT, and latterly Erase Errata, Sonic Youth, Scissor Girls, Karen O, Nisennenmondai etc.

Now: I didn’t include any illustrations with the writing, because my grasp of decent visual art is comparable to Boris Johnson’s grasp of his handlebars after a heavy night out. But apparently it would be nice to have some.

Therefore: I’m looking for suitable images – photographs, illustrations, cartoons – for inclusion in the chapter. Anything relevant considered especially if it pertains to the bands mentioned. Full credit given, further details on request, please pass this on if you can think of anyone who’d care. Thank you.

Also: it is my birthday. I’m going to celebrate with fresh air and daylight.

Musicians and authors in the digital world.

I have an essay in this month’s New Welsh Review on the impact of digitization on publishing as compared to the music industry. I wrote it without anticipating FutureBook’s overview, which does commendable spade-work explaining the situation’s background, present and future, whereas I mostly just snark from the sidelines.

In essence: big publishing houses have, like velociraptors, watched and learned from the music industry’s floundering and are now primed to do better out of e-publishing. My piece also covers the Indelicates’ ‘post-internet’ site Corporate Records, the pros and cons of self-publishing, the unpleasant prospect of e-books becoming the new disposable mass-market paperbacks while physical product becomes concentrated on luxury hardbacks, and why Hodder’s dubious flipback format is the literary equivalent of the MiniDisc.

Perhaps ironically, it’s unavailable online, but the print copy is accessible in all good stockists, or at least all Welsh ones.