Tagged: music journalism

Triptych: Three Studies of Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible is my next book, co-written with Daniel Lukes and Larissa Wodtke, coming out in February next year from Repeater Books.

My bit looks at the politics and pop culture of 90s Britain, growing up in post-industrial Wales, class and gender and the rest of my usual stuff, and how the album fit or didn’t fit into that context.

(Obviously a cultural materialist analysis of the Manics’ least commercial album is the one thing the world needs right now.)

I’ve just finished reading Sylvia Patterson’s book on her life as a music journalist and felt instantly compelled to recommend it. It’s very like Viv Albertine’s memoir, being full of not only the silliness and thrill of being young and loving music, but also casually devastating insight into personal tragedy and cultural shift – and how often the two are combined.

Patterson was never one of my particular favourites growing up (totally unfairly – I think I found her Smash Hits-raised pithy exuberance irritating because I was an insufferably morose teenager, and also I always tribally preferred Melody Maker to NME) but I like her writing a lot more in retrospect and it’s actually clearly been more of an influence on me than I’d realised – her deployment of incisive epithets especially. There’s something distinctly feminine, too, about both her and Albertine’s style of autobiography, and it seems to be specifically an older woman’s thing – this isn’t confessional writing so much as unassuming honesty, a certain understated wisdom and maturity, a settlement with the self that renders obsolete the need to front.

Patterson also captures the death of a particular ideal of music journalism – and of a whole approach to music – that I think people my age may be the last to truly remember. Before the internet as both community and culture/media platform, we were atomised, connected by a music press which was hugely – unimaginably, now – important as a site of cultural discovery, debate and conflict, and for feeling as though you belonged to something bigger, something beyond yourself. This way of thinking and writing about music and culture was formative for me. It was the only thing I saw any sort of sense in or any kind of point to. I grew up wanting to do the same thing, but I grew up into a changed world where the prospect of doing so no longer existed in any stable or secure way. (I mean, I did so regardless; Clampdown is (an attempt at) exactly that kind of writing and I was lucky to find the right publisher for it – indeed, the only imaginable publisher for it.)

There’s been a notable amount of 90s revisionism since that book, as though a particular generation can now see clearly enough at twenty years’ remove to try and weigh up what’s occurred as well as tell their own story. There’s a bit in this book where Patterson recalls her younger self finally recognising the NME’s transformation, round about ’98, into “the indie Heat“, and reading it made me feel, like it was yesterday, that sense of incredulity and personal betrayal that characterised the still-spectacular decline of the 90s music press. But her description is at the same time entirely aware of how absurd and inexplicable, how deeply daft it is to even care that much – about music, about bands, about magazines, about words in print, about anything that isn’t a capitalist imperative.

But we did care. For me for a stretch of my formative years – far shorter in retrospect than it felt at the time, maybe no more than four years or so – this kind of thing was everything. As this book confirms and brilliantly documents, there was a definite and decisive cultural shift to the right in the 90s, in which we lost something that hasn’t really been replaced. Things still feel poorer for it.

Elsewhere.

Post-punk: a plug and a playlist.

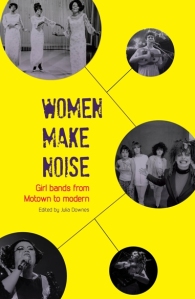

I am in print this month, having written a chapter on women in post-punk for Julia Downes’ new history of the girl band, Women Make Noise. A surprisingly difficult part of this was establishing what we talk about when we talk about post-punk. Post-punk’s disorderly, subversive and category-resistant nature has seen it marginalised in accounts of its era, although the past few years have produced a handful of useful retrospectives, as well as the early-2000s revival of post-punk musical techniques which, if you still can’t explain what it is, at least make it easier to explain what it sounds like.

For me, a large part of post-punk’s significance was that it seemed to involve an unprecedented amount of women as artists, fans, critics and ideologues. Extending the gains of punk’s emphasis on DIY culture, accessibility and amateurism, post-punk women were able to take their bands in experimental and innovative directions. Post-punk’s ideological concern with the politicisation of the personal, and with identifying and promoting authenticity in the face of popular cultural stereotypes, lent itself to exploration from a feminine and feminist angle, resulting in lyrics which demystified and deconstructed conventional femininity, love, sex and romance, and which analysed social and cultural pressures on women or the tensions of personal relationships in implicitly political ways. Continue reading

Cover Girls and Typical Girls

There were several predictable bones to pick with this piece in which former editors of the New Musical Express select their most noteworthy covers. The feature leaves out a lot of the former Accordion Weekly’s history, notably anything prior to the late 1970s, but what struck me most about the covers chosen was the disparity between the first one and the last. Pennie Smith’s 1979 cover shot of the Slits, then a relatively obscure and resolutely uncommercial dub-punk girl-gang, mudlarking in the grounds of their Surrey recording studio, was part of a set which became a defining image of the band, notably through being used on the cover of their debut album Cut. This article looks briefly at the controversy generated by the images themselves, and how it relates to subsequent and current presentation of women in the UK music press. Continue reading

A quick request (re. images of women in post-punk).

So: I’ve written a chapter on female post-punk musicians* for a forthcoming women-in-music book. I mostly talk about the Slits, the Raincoats, Linder Sterling, Lydia Lunch (unavoidably), ESG, the Au Pairs, Delta 5, Pauline Black, Barbara Ess, Ut., Mars, the Bush Tetras, the Bloods, Malaria!, Kleenex/LiLiPUT, and latterly Erase Errata, Sonic Youth, Scissor Girls, Karen O, Nisennenmondai etc.

Now: I didn’t include any illustrations with the writing, because my grasp of decent visual art is comparable to Boris Johnson’s grasp of his handlebars after a heavy night out. But apparently it would be nice to have some.

Therefore: I’m looking for suitable images – photographs, illustrations, cartoons – for inclusion in the chapter. Anything relevant considered especially if it pertains to the bands mentioned. Full credit given, further details on request, please pass this on if you can think of anyone who’d care. Thank you.

Also: it is my birthday. I’m going to celebrate with fresh air and daylight.

Never Mind the Bollocks.

Music books written by women, list of. Go, compare, question, critique.

Why don’t more women write about music – or do they? And why don’t more women write about Dylan? It can’t just be me and Sady Doyle.

Also, with due apologies for more self-promotion – I don’t think I’ve mentioned this here yet, but I’m currently writing a chapter on female postpunk musicians for a forthcoming anthology on that shy and elusive creature, the girl band. This book will be a contender with or without my contribution though. Watch this space.

Can Adele and her Marketing Men change the face of Women in Music?

Written for Bad Reputation, 1.6.11

*

Poor old millionaire superstar Adele, eh? No sooner has the dust settled on the furore over her objections to being a higher-rate taxpayer, than she gets thrown into the vanguard of another of those putative Real Women in Music revolutions. A mere three years after she started out, and after just seventeen weeks of her second album at Number One, it appears to have suddenly dawned on Richard Russell that Adele exemplifies all that’s healthy and hopeful in the otherwise dire and overheated state of contemporary pop. Continue reading

Stop me if you think that you’ve heard this one before.

Simon Reynolds has decently condensed his new ‘un into a Guardian article:

The book is not a lament for a loss of quality music – it’s not like the well-springs of talent have dried up or anything – but it registers alarm about the disappearance of a certain quality in music: the “never heard this before” sensation of ecstatic disorientation caused by music that seems to come out of nowhere and point to a bright, or at least strange, future.

I don’t wish to dollop even further layers of irony on top of this particular trifle – but we’ve been here before, too, haven’t we? This is repetition, if not revival. What Reynolds castigates as ‘retromania’ has been sporadically identified throughout the past decade, most perspicaciously by several of my mates around about the point at which the third pint starts to make its presence felt, because we’re old enough to remember when revivals seemed novel, if only because this was the first we’d heard of them. Continue reading

Women, Men, and Music: the XY Factor

Let me begin with some residual New Year bonhomie by saying that the New Yorker‘s Alex Ross is not the problem here. It’s just that you sometimes need to take an inventory of the symptoms before starting on the cause. Last month I attended a talk by Ross on the release of his latest book. The talk and the discussion which followed were interesting enough, but throughout the evening I couldn’t help noticing that, although there were several women in attendance, every single raised voice in the room was male.

Gaye Advert and the Great Cock ‘n’ Balls Swindle

‘Sexuality in Rock’n’roll is one more area weighed down heavily by its history and language. While none could or should deny the aspects of sexual interest and thrill inherent in live music, the performance space is problematically male-dominated.’ – Ian Penman, NME, 1979

‘I really wish that I’d been born a boy; it’s easy then ’cause you don’t have to keep trying to be one all the time.’ – Gaye Advert, 1977

Women in bands, when under the media spotlight, often find themselves swindled out of due credit by virtue of their gender. If they’re not being accused of clinging to the coattails of their backing boys to disguise their own lack of musical ability, they’re being judged on their aesthetic appeal to the exclusion of anything more relevant. It’s disappointing to observe how ubiquitously this principle applies. Even in the midst of punk, as girls picked up guitars, bass, and drumsticks, taking the stage alongside boys as more than cooing vocalists or backing dancers, they attracted that lethal combination of critical suspicion and prurient interest.

I love punk partly for the number and variety of women it involved and the freedom of expression it offered them. I loved X-Ray Spex – a Somali-British teenage feminist demagogue whose vocal screech swooped like a bird of prey over twisting vistas of saxophone. I loved the Slits and their slippery, shuddering dub-punk hymns to the tedium of sex and the joys of shoplifting. And I loved Gaye Black, bassist for The Adverts and widely regarded as punk’s first female star.

Continue reading

Being a female music fan online and offline

While the 1990s weren’t the greatest decade for feminist comings of age, as a small-town girl who loved her music, I didn’t do too badly. I’d grown up on the leftovers of punk, awed and enthralled by women like Poly Styrene, Patti Smith, Ari Up and Gaye Advert. Closer to home, I had Shampoo’s deadpan, dead-eyed bubblegum-punk and Kenickie’s bracing uber-proletarian blend of grit and glitter.

Sleeping with the NME: how the British music press picked up a dose of the crap

Back in the speed-addled, black-eyelinered days of my early adolescence, the NME had bite, balls, and brio. And it still had nothing on Melody Maker. Every Wednesday lunchtime saw me, lower lip bitten with anticipation, heading into town to snag the latest issue of each; our newsagent stocked all of three copies, and I never found out who, if anyone, bought the others. For me and others like me – small-town, provincial or suburban kids beyond the pale of London’s bright lights, with mass internet access as yet untapped, gazing wide-eyed on stories of the gig-circuit – the weekly music press served as a channel of cultural discovery and as the cool older brother we didn’t have.

So scalpel-sharp was music journalism at that time that I can still recall features, reviews and even some lines from them, both the building up and the demolition jobs. Taylor Parkes skewering the Cult of Richey with a cutting You don’t deal with depression by making it the focal point of your personality – you have to rage against it, perpetually. Neil Kulkarni’s still-astonishing wrecking-ball swing at Kula Shaker and the post-Oasis consensus (Crucially, retro-accusations are less important than pointing out how deadly dull the bulk of this LP is, in a way that only true scumcunt hippies can be: “K” … shits itself in fear of the future (1973) and stinks of living death) which at the time made for what felt like genuinely revolutionary reading.

And yes, it was fucking political. NME’s former editor Neil Spencer claims the pre-Britpop music press treated music as part of a wider oppositional culture in which the angry and intelligent political consciousness of bands like S*M*A*S*H and Asian Dub Foundation was considered an asset rather than an embarrassment. Encompassing the world beyond music, as well as music beyond the mainstream, the NME and MM took on fascism, racism, sexism, Morrissey, Thatcher and Blair. More sophisticated than the sledgehammer sludge of many more overtly political publications, a certain left-wing sensibility shone through the best of their writing like sunlight through stained glass.

But, as every Libertines fan knows, the best things never last. Whereas Spencer blames IPC for the NME’s political castration, the decline and fall of Melody Maker has been generally attributed to its enforcing of what Parkes and Kulkarni identified as a ‘kid’s taste’ PR-led consensus and its aimless chasing of a demographic which already had Smash Hits. The latter half of the Nineties, with its rapid turnover of scenes and genres, saw the paper hitch its wagon to a succession of shortlived stars, including Nu-Metal and, notoriously and prematurely, RoMo, before its last-gasp glossification and eventual merger with NME.

The gulf between then and now is perhaps most apparent in the NME’s current attitude to the industry and its failure to adequately define itself against a cultural mainstream. Whereas Kulkarni trained his sights on mainstream radio and MTV as peddlers of the creativity-crushing Kids Consensus, the NME now revels in unholy commercial alliances, sponsorships and tie-in deals. The dangers inherent in this trend were exemplified in 2005 by the controversy over its Top 50 albums list. The ensuing furore both dealt a blow to what little of NME’s credibility remained, and proved that the paper had fallen prey to a system largely built on mutual backscratching where, yes, there’s only music so that there’s new ringtones.

The NME’s present incarnation – a dishwater-dull industry cum-rag with an editor who resembles a spoon in a suit – is of course merely reflective of a more widespread erosion of choice and illusion of independence which currently infects most aspects of culture and politics. The music industry in particular will always aspire to Johnny Rotten’s vision of ‘a bloated old vampire’, and nothing has filed down its fangs so much as the relocation of sharing, discussion and critical analysis of music to online publications, networks and forums. As for the NME, appearing in its pages these days is akin to standing on a moonlit Transylvanian balcony in a billowing nightdress bellowing ‘Come and get me, Vlad!’; you’ll be drained dry and thrown aside for something juicier within weeks. Hope lies in the blogs.