Tagged: Rhian E Jones

Under My Thumb: Songs That Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them

Under My Thumb is a collection of women’s music writing, edited by Eli Davies and me, in which contributors discuss being fans of politically dubious music, artists and songs. It’s out in October from Repeater Books and available to pre-order now.

Artists covered, in-depth or in passing, include: Dion and the Belmonts, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, Carole King, The Crystals, Phil Spector, Bob Dylan, Pulp, Gary Puckett & the Union Gap, Anni-Frid Lyngstad, The Rolling Stones, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, David Bowie, Pure Prairie League, Rod Stewart and The Faces, Eddie Cochran, AC/DC, Van Halen, Guns ‘N’ Roses, L7, Elvis Costello, murder ballads, Nick Cave, Sir Mix-a-Lot, Run the Jewels, 2Pac, Eminem, Weezer, The Divine Comedy, Jarvis Cocker, Combichrist, Jay-Z, The Libertines, My Chemical Romance, Fall Out Boy, Kanye West, The-Dream, Swans, Taylor Swift.

Full list of contributors: Amanda Barokh, K. E. Carver, Marissa Chen, Zahra Dalilah, Eli Davies, Judith May Fathallah, Anna Fielding, Alison L. Fraser, Laura Friesen, Beatrice M. Hogg, Rhian E. Jones, Jacey Lamerton, Abi Millar, Emily McQuade, Frances Morgan, Christina Newland, Elizabeth Newton, Stephanie Phillips, Nina Power, Charlotte Lydia Riley, Kelly Robinson, Jude Rogers, Jasmine Hazel Shadrack, Em Smith, Johanna Spiers, Manon Steiner, Fiona Sturges, Rachel Trezise, Larissa Wodtke.

Out now: Triptych, Three Studies of Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible

Triptych: Three Studies of Manic Street Preachers’ The Holy Bible is my next book, co-written with Daniel Lukes and Larissa Wodtke, coming out in February next year from Repeater Books.

My bit looks at the politics and pop culture of 90s Britain, growing up in post-industrial Wales, class and gender and the rest of my usual stuff, and how the album fit or didn’t fit into that context.

(Obviously a cultural materialist analysis of the Manics’ least commercial album is the one thing the world needs right now.)

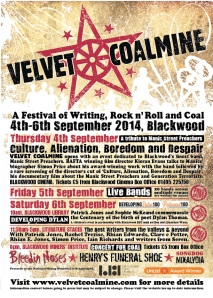

Velvet Coalmine, the festival: in Blackwood, 4-6 September

The first Velvet Coalmine Festival, featuring the best of Valleys music, art and literature, will be happening next weekend. Like Camden Crawl, but with more coal.

Among loads of other acts, I will be talking to the excellent Rachel Tresize about the ins and outs of having been a female Manics fan.

“Velvet Coalmine aims to create a platform for music, writing and ideas in the Blackwood area that allows our voice to be heard and celebrated. It allows our stories to be told and communicated to the wider world without censorship and our cultural heritage and identity to be expressed on its own terms without interference, without suppression and without agenda. The history of the Valleys is littered with exploitation, neglect and indifference but has proved a birthplace to a myriad of thinkers and pursuers of social justice and in an era when Old Etonian privilege continues to shape and influence decision-making and politics in the UK, creating an arts festival influenced by the radicalism of the 1984-85 miner’s strike and the Centenary of the Senghenydd mining disaster feels both timely and appropriate.”

Full listings and contact details can be found here on the website. Come on down.

Links to things I’ve written elsewhere.

1. ‘Crumbling Pillars of Feminine Convention’ – on Viv Albertine’s memoir Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys. Sex, punk, feminism, the usual.

2. ‘Living Fast: Revisiting Oasis’ Definitely Maybe‘ – on Alex Niven‘s Oasis; 90s Britain (bad) and 00s Britain (slightly worse); pros and cons of ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’ as life philosophy.

3. Retrospective on the 20th anniversary (!) of The Holy Bible, the summer of 1994 and the travails of being a teenage girl, available in the new issue of Planet magazine. Well worth buying a hard copy as it also contains, among other things, a fascinating article on the history of cross-dressing in protest. My piece is accompanied by the photo below, taken some time in the mid-90s when I had taken to hand-spraying a glittery hammer-and-sickle onto my dress, as was the style at the time. Outfit is not currently, as one correspondent suggested, housed in the museum of Welsh folk art.

On talking about pop when you want to talk politics.

Alex Niven’s book on Oasis’ Definitely Maybe is out now and worth your time. It’s a book about working-class art, working-class politics, and the decline of both in Britain since the 90s, but there’s no denying the fact that it’s also a book about Oasis. So for the purposes of this post, which isn’t about Oasis, let’s talk about Oasis first:

Yes, it’s alright if you think Oasis were shit. Yes, Oasis went downhill fast – almost immediately, in fact. Yes, Oasis were a more ‘authentic’ version of the freewheeling should-know-better casually chauvinist Lad that, in Niven’s term, the ‘bourgeois wing of Britpop’ attempted to pantomimically portray, and no, this wasn’t necessarily a good thing. Music press, tabloids and lad-mags in the 90s lionised the Gallaghers’ laddishness as part of a tediously retrograde cultural discourse that was intent on rolling back the ‘politically correct’ gains of the decades before. This same discourse imposed a false dichotomy of class, in which Oasis’ supposed proley authenticity was linked with loutish ignorance and excess, while experimentation, education and glorious pretentiousness were presented as the preserve of the middle class. So yes, Oasis were damaging. But more by accident – or by deliberate exploitation by a largely middle-class cultural industry – than by design.

And yes, there was more than Oasis happening in the 90s. The issue here is that no other band got so big, so phenomenally quickly, and the question is whether anything interesting can be said to explain that – you know, beyond the not-even-trying paradigm of “people like Coldplay and voted for the Nazis; you can’t trust people, Jeremy”. The book’s background argument on this, to which I am a rock-solid subscriber, is that, as 90s politics capitulated to a post-Thatcher consensus, a more subversive, anti-establishment spirit persisted in early-90s pop culture – including early Oasis alongside the Manics, Pulp, Kenickie etc – which then got flattened under Cool Britannia, Blairism, and Britpop’s imperial stage. Overthinking it? Yeah, if you like. Better than underthinking it, mate. Continue reading

From Olympia to the Valleys: What Riot Grrrl Did and Didn’t Do for Me

[This essay first published in the Wales Arts Review, with artwork by the tremendous Dean Lewis.]

With riot grrrl now approaching the status of a heritage industry, not to mention Courtney Love’s current incarnation as the post-grunge Norma Desmond, it can be hard to recall that both of them helped me find my feminist footing on the slippery rocks of a ’90s girlhood. This is a roundabout remembrance of how it happened.

I.

The arts have long been a space for radical expression by women, even if the extent of that radicalism has often gone under-acknowledged. In 1915, the author and journalist Dorothy Richardson produced Pointed Roofs, credited as the first English stream of consciousness novel, using an innovative prose style which she saw as necessary for the expression of female experience. Virginia Woolf observed that Richardson ‘has invented, or, if she has not invented, developed and applied to her own uses, a sentence which we might call the psychological sentence of the feminine gender’. If Richardson’s challenge to linguistic convention in her writing has musical counterparts, one of them is the ‘new, raw and female’ sound made possible by post-punk. Punk removed barriers of precedent and technical expertise to engagement in music, enabling trips into less-charted musical and lyrical territory. But it was in the subsequent voyage of discovery that was post-punk that punk’s revolutionary potential really bore fruit, and the untried, experimental nature of post-punk music was particularly suited to women.

Bonnets and Bolshevism

1. For my next trick in the arena of niche overthinking-it monographs, I am going to be writing a book on the Rebecca riots. There have already been magisterial studies of the movement which have focused on its political and economic aspects, but I am going to look at its social and cultural aspects, and the ways in which it had more variety, more politics, and more of Old Weird Wales than is generally acknowledged.

To include: why there was a bit more to the movement than hill-farmers smashing up tollgates in bonnets, petticoats and false beards; the nature of Welsh resistance to early industrial capitalism (as touched on in this post); contemporary ideas of gender and the early Victorian undermining of female social and sexual agency; how Rebecca’s image became a national ‘idiom of defiance’ – basically, a meme – and wider issues hopefully relevant to today, eg “rough” versus “respectable” protest; the traditions of masked and anonymous protesting; and how popular culture can be integrated into popular resistance.

Don’t worry, I’m fully aware that this book will be of interest to about four people at a push.

*

2. The last time I was in the House of Commons in any official capacity, I was taking students to lobby against the introduction of top-up fees. Our side having narrowly lost that vote, I then got massively drunk in the ULU bar, decided to give up student politics as a mug’s game, ranted at a Sky News crew and eventually had to be carried out to a taxi by members of my delegation.

Last month I attempted to conduct myself with greater dignity, and spoke on this Zero Books panel. Strike! magazine wrote up the evening here.

Intersectional Feminism, Class, and Austerity

Last week I went to a conference at Manchester Met to speak (broadly) on intersectional feminism, alongside the excellent Reni Eddo-Lodge. The event had some useful and interesting contributions, given in an atmosphere notable for constructive and supportive discussion, and for critiquing work done previously rather than seeking to reinvent the feminist wheel. Below is a transcription of the talk I gave. It works as both a synthesis of things I’ve written previously on feminism and class, and as a step towards articulating how my own type of feminism developed (clue: this year it’s thirty years since the Miners’ Strike). It also, in a personal best, contains only one use of ‘autodidact’, none of ‘hegemony’, and no mention of the Manic Street Preachers.

Introduction

The concept of intersectionality has a long history, and has informed the political work of women from Sojourner Truth in 1851 to Selma James’s 1975 pamphlet ‘Sex, Race and Class’. In 1989 Kimberlé Crenshaw’s use of the term emphasised how women of colour experience multiple systems of oppression, and how their experiences and voices are frequently marginalised or erased, even within feminist or anti-racist discourses which aim at justice or liberation. Intersectionality has been the subject of much recent discussion within feminism, some of which has dismissed the concept on the grounds of its supposed academic obscurity and irrelevance to ‘ordinary’ people. I will dispute this dismissal.

The aspect of intersectionality I’ve written most about is the tension between class politics and some of the ways in which contemporary UK feminism is expressed. I’m not suggesting that class is the only dimension of oppression, or the only one worth exploring, but I do see class as something fundamental, and as something which intersects significantly with both race and gender. These interactions are particularly visible in the debate on ‘chavs’, which I see as a point at which class prejudice crosses over with several others. I will look at that debate and at the surrounding context of neoliberalism and austerity in which it takes place. I will then look at how responses to this debate, in attempting to rehabilitate working-class identity, have instead constructed exclusionary models of class based around the idea of the white male worker. I will then finally talk about how the calls for feminism to make itself accessible beyond white and middle-class women, has tended to involve negative or condescending assumptions about working-class women and their capacity for education, political consciousness and organisation.

Radical History: the London Corresponding Society vs the Privy Council, 1794

The long essay linked here is something I wrote years and years back, as an undergraduate, and I have finally now got round to finding somewhere useful for it to live online. It is set at a time, in the late 18th c. Britain made famous by Blackadder the Third, of a rise in popular radicalism, political organisation by artisans and labourers, and campaigns to extend the franchise. The essay looks specifically at the process, in many ways unprecedented and bizarre, whereby organisers of, participants in, and vague or occasional sympathisers with campaigns for popular democracy were rounded up and questioned by the highest echelons of a hostile, uncomprehending and paranoid state. (Think the Thatcher cabinet doggedly interrogating not only the NUM leadership but also the whole audience of a Coal Not Dole fundraiser, or, idk, the present cabinet interrogating UK Uncut.)

Like many things which can be given that kind of build-up, the actual material of the interrogations can be a surprisingly dull read, but there were several aspects that I found, and hopefully the general reader will find, of interest, amusement, and continued relevance, viz:

To begin with, despite the mass arrests of radicals being justified by panicky accusations of treason, this accusation wasn’t a comfortable fit with the evidence. Treason in 1794 specifically related to plotting against the reigning monarch rather than the government, and the societies agitating for popular democracy, despite a preoccupation with Revolutionary France, were invariably concerned more with the latter than the former. The 1794 interrogations and the trials which followed, however, were an abrupt step in a long-term shift of the legal location of sovereign power towards Parliament, in which the extra-parliamentary advocacy of constitutional change became construed as a treasonable practice. In 1795, the new Treason Act defined as traitors not only all those who ‘compassed or devised’ the death or deposition of the monarch, but also those seeking ‘to intimidate or overawe both Houses or either House of Parliament’.

Relevant today? Take your pick. My thanks to the John Thelwall Society, who are great.

Talking Treason? John Thelwall and the Privy Council examinations of the English Jacobins, 1794

* E P Thompson: “But for spies, narks and letter-copiers, the history of the English working class would be unknown.”

** M. Philp, ‘Intrusions’, History Workshop Journal, 65 (2008), pp. 220-7

Post-punk: a plug and a playlist.

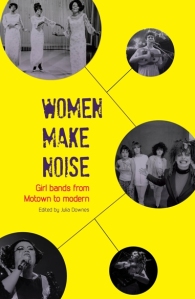

I am in print this month, having written a chapter on women in post-punk for Julia Downes’ new history of the girl band, Women Make Noise. A surprisingly difficult part of this was establishing what we talk about when we talk about post-punk. Post-punk’s disorderly, subversive and category-resistant nature has seen it marginalised in accounts of its era, although the past few years have produced a handful of useful retrospectives, as well as the early-2000s revival of post-punk musical techniques which, if you still can’t explain what it is, at least make it easier to explain what it sounds like.

For me, a large part of post-punk’s significance was that it seemed to involve an unprecedented amount of women as artists, fans, critics and ideologues. Extending the gains of punk’s emphasis on DIY culture, accessibility and amateurism, post-punk women were able to take their bands in experimental and innovative directions. Post-punk’s ideological concern with the politicisation of the personal, and with identifying and promoting authenticity in the face of popular cultural stereotypes, lent itself to exploration from a feminine and feminist angle, resulting in lyrics which demystified and deconstructed conventional femininity, love, sex and romance, and which analysed social and cultural pressures on women or the tensions of personal relationships in implicitly political ways. Continue reading

Great Rock n Roll Swindles: Rethinking Justine Frischmann

This post was mostly inspired by the complaint of my fellow Bad Reputation member Sarah J that, when the subject of Elastica comes up, the band are frequently dismissed outright as flagrant copyists led by Britpop’s version of Lady Macbeth. In fairness, I spent most of the 90s thinking the same thing. God, I used to hate Elastica. Willfully amateur slack-jawed rip-off merchants whose frontwoman seemed to exist only as a drawly amalgam of her indie boyfriends (hair by Brett, boots by Damon), whose competency in snagging the catchiest bits of post-punk couldn’t disguise how irritatingly thick and bland they were in all other respects. Right? Right. Now that I’m no longer a chippy thirteen-year-old convinced that people with trust-funds can’t make good music, I’ve been reassessing Elastica. Continue reading

On liking American Psycho, slight return.

The last time I wrote that yes, I did like American Psycho, and no, that wasn’t because I’d only seen the film, I was pleasantly surprised to hear that other women felt similarly, but I’m aware that we’re still a minority. American Psycho proved controversial even before its release, its unedited manuscript pushed from publisher to publisher, leaked extracts from it incurring public outrage, and its eventual appearance leapt upon by critics with the single-minded speed of a rat up a Habitrail tube. In terms of people judging the book without having read it, not a great deal seems to have changed. Continue reading

A rushed response to ‘survival in the cracks’.

I had only one real beef with the excellent Paul Mason’s most recently printed reflection on ‘the graduate without a future’, but it’s the same beef I have with almost every recent lamentation on the state we’re in: lack of attention to class as key. Given Mason’s interesting and not especially privileged background, it seemed a particularly surprising omission. While of course I appreciated the article’s update on how there’s still no future, but there might be some putative entrepreneurial ‘survival in the cracks’, stringing beads together on a collective farm then selling them through The New Inquiry (I paraphrase) – it’s still the case that all graduates are not created equal, and some are still more equal than others. Correct me if I’m wrong (really, do correct me if I’m wrong), but while very, very obviously, it’s still shit to be a graduate right now, surely it’s marginally more shit to be a poor graduate?

Take the Coalition’s recent wheeze, the proposed cut in Housing Benefit for those under 25, which has been widely predicted to herald jobless or low-paid graduates being thrown back to live on the largesse of their parents, or failing that, on their settee. Is there really no discernable difference in the future that awaits a graduate returning to a post-industrial unemployment blackspot, and that awaiting one whose family are able and willing to subsidise their rent and support them while they work unpaid internships? Those graduating with wealth and connections are surely likely to retain their privileges? Take, too, the withdrawal of EMA and cutting of university funding, which is serving to entrench the idea of education as something undesirable because unaffordable, not something which can serve as a route out of poverty and a broadening of horizons.

Also, as several people stressed below the line on Mason’s article, this focus on the plight of the graduate – pitiable, emblematic, and potentially revolutionary as it may be – is part of a broader narrative whereby conditions which have always been likely for those at the socio-economic sharp end are becoming something to which the middle class, and their graduating sons and daughters, are increasingly exposed. The resulting shrieks of indignation are amplified in the media. While it’s true and valid to note that the current economic model is visibly failing, there are those for whom it has never really worked, and whose struggles with it scarcely ever receive broadsheet coverage. In the grand scheme of things, and especially right now, I’m not sure whether this is too insignificant a complaint to make, or whether it’s the only complaint worth making.

Standard, and Poor.

The forward march of labour halted.

Two things I wrote recently on the music, culture and politics of that weird, desultory decade, the 1990s:

1. Up Close and Personal: Lost Girls

For the decade blogs, my Tesco Value Greil Marcus number on gender, class, Britpop and everything after, chav-hysteria and narrowing of access.

2. Rebel Music #5: Manic Street Preachers

For New Left Project, a cleaned-up and condensed version of my customary closing-time rant on the politics of the Manic Street Preachers. I know I fail to mention, eg, Soviet chic, or Castro, or self-harm and anorexia, or the band’s appeal to teenage girls, or anything after This is my Truth Tell me Yours. It’s not that they’re irrelevant, they’re just relevant to a different article. Or possibly a whole book.

Seen a lot of bullshit, I wonder what’s next.

I mean, I don’t hate ‘Ill Manors’. I did at first, almost instinctively, but I like it more the more I hear it. I also find it easier to take in without the video. (Also that sample of ‘Alles Neu’ gives me flashbacks to 2008 when an ex of mine would repeatedly play it; fair enough you can never escape your past, but I don’t think anyone expects theirs to pursue them in the form of Peter Fox.) Still, the alacrity with which it’s been leapt on as the protest song we’ve all been waiting for has slightly surprised me, even though it’s more vital and switched-on than, from a year ago:

and – maybe – more accessible than, lest we forget its glory, and the possibility of ‘TOSSAH’ being the present Secretary of State for Health’s epitaph:

I’m not convinced ‘Ill Manors’ taps the roots of the present malaise with any greater degree of elegance and articulacy than, say, Dizzee Rascal did in 2003:

Something that seemed to get overlooked in the past few years’ constant referencing of a ‘lost generation’ and of ‘graduates without a future’ was that, lower down the socio-economic scale, little had substantially changed. For many with memories that stretch beyond the credit crunch, the last recession and the last UK election, attaining comfort and security has always been a struggle, prospects have never been great, and home-owning and independently funded internships, for instance, have always been implausibilities. For many there has always been poverty, precarity, petty criminality and police animosity, even if the past few years have exacerbated their reach and increased their visibility, resulting in their sudden horrified pointing out by those who might previously have missed them due to being shielded by better prospects and broader horizons.

Although ‘Sittin’ Here’ is nearly a decade old, running through it is a very relevant current of chill and clampdown. But ‘Sittin’ Here’ is not a ‘protest song’. It’s a laconic, fatalistic and very mature anatomy of socio-economic melancholy. Simmering but unspoken discontent, alienation, anomie and lacking signs of positive change have for a long time been a way of life to which many have of necessity had to reconcile themselves, not a sign of the final crisis or a spur to mounting the barricades.

I guess timing is everything, though. There’s an inescapable sense (as in, one is constantly given the impression) of right now being either turning-point or snapping-point. The recently added ingredient of a recklessly ideological government seems to have clarified and amplified things that have been the case for a while, made them more immediate and obvious. ‘Ill Manors’ does validly externalize rather than brood over its anger and confusion, and doesn’t assume some golden age of mortgages for all and paid internships cruelly wrested from this generation by everyone over the age of twenty-four. ‘We’ve had it with you politicians you bloody rich kids never listen / There’s no such thing as broken Britain we’re just bloody broke in Britain / What needs fixing is the system not shop windows down in Brixton / Riots on the television you can’t put us all in prison’ is a very hard line to argue with.

Privatize everything > Occupy the tollgates.

You’re all joking about the roads being next for privatization, aren’t you. Aren’t you. Oh, you’re not.

It’s just that in another lifetime, one of toil and blood, I did my whole thesis about a little local difficulty which centred around privatized road networks: the ridiculous/amazing “Rebecca riots”.

Part of what I liked about the study of history was that it did occasionally seem – by no means always, of course – as though society in general wasn’t too disparate, atomized, hopelessly confused, thick, or arrogant to learn from its mistakes.

For example: ‘Wow, at least private roads wouldn’t be an option /these days/’, I’d often muse, back in the day, having conducted hours of research and written thousands of words about how badly it had all worked out in the face of popular insistence upon public utilities being kept for the collective good rather than left to the profiteering of incompetent private companies.

(The Rebecca riots were a lot more complex than that, obviously, hence my studying them in the first place, and my bringing in their use of masking, cross-dressing, ritually smashing stuff, inter-class cooperation, liminal states, gender essentialism, and the disparity between lived experience and political and media discourse – don’t worry, neither the Taxpayer nor Hard-Working Families were paying for me to study any of this – but the general resentment of private ownership as leading to general neglect and profiteering holds true as a contributing factor – as indeed it holds true over two hundred years on.)

I’m sick of saying we’re being taken back to the Victorian age, but this? Is the government just trolling, now?

Or, with less (or perhaps more) conspiracist fervour: RT @bengoldacre Wouldn’t it be a shame if this distant roads nonsense distracted you from the Lords’ final vote on #NHSbill.

Can’t get out of bed? Don’t bother.

So little allure does contemporary music hold that I forgot the Brit Awards were taking place this year, and spent last Tuesday evening in the bowels of a club in that odd hipster-troubled enclave north of Oxford Street, watching Tim Burgess launch his autobiography. Well, we all have to pay the rent somehow.

You recall the rash of soi-disant Minor Indie Celebs which infested post-Libertines London? If you don’t, I wouldn’t blame you; they were peole like the Queens of Noize, or The Holloways. But if you do, you might also recall that a secondary feature of this period was the reemergence of several 90s indie also-rans (now there’s a tautology for you), lurking in support slots and at DJ sets, most often in the vicinity of Barat and less frequently of Doherty. Apparently the 90s are now officially back – finally! The 90s revival has been ‘impending’ for at least four years – which at least means the 80s aren’t back any longer, unless you count things like politics, economics, society and culture. But the 90s never really went away, their cultural detritus over the past decade continually bobbing to the surface like something unflushable.

Tim Burgess is harmless enough, of course, and to criticise him feels akin to cudgelling a seal-pup. The book, like the Charlatans, is probably a perfect example of its inoffensive, tolerable, un-vital type. After exacting dissections of Blair and Britpop, the 90s as the subject of memoir and history doesn’t even have the shock of the new, although a wider perspective on the music of the period does show what an odd time it was, post-Thatcher and pre-Blair, briefly and freakishly fertile before the greywash. And even afterwards: this happened at a Brit Awards ceremony in the 90s, and so did this. Privatised and atomised examples of protest, sure, but you know, if I somehow missed Adele making a Bastille-storming speech on Tuesday about the scandal of government money being siphoned off by private companies who maintain their luxurious lifestyles off the backs of the unemployed, then do correct me.

Anyway, the only point I vividly recall about Tim Burgess’s autobiography was the repeatedly-mentioned chapter entitled – and I haven’t checked the spelling here – ‘Cocainus’. ‘It’s a portmanteau word’, explained the author, with no great necessity, ‘formed from the words “cocaine” and “anus”‘. Rarely have the 90s been so succinctly summed up.

*

Last night a DJ ruined my life: a Valentines Day playlist

My resolutely unromantic Valentines Day playlist this year consists of:

– Robots in Disguise, ‘Chains’

– Einstürzende Neubauten, ‘Jet’M’

– The Bush Tetras, ‘Too Many Creeps’

– The Slits, ‘I Heard it Through the Grapevine’

– Amy Winehouse, ‘Back to Black’

– Pulp, ‘Bad Cover Version’

– Magazine, ‘Permafrost'(apocalyptic version off one of their Peel sessions)

– Super Furry Animals, ‘Juxtapozed With U’

It can be listened to here on 8tracks, if you like.

A quick request (re. images of women in post-punk).

So: I’ve written a chapter on female post-punk musicians* for a forthcoming women-in-music book. I mostly talk about the Slits, the Raincoats, Linder Sterling, Lydia Lunch (unavoidably), ESG, the Au Pairs, Delta 5, Pauline Black, Barbara Ess, Ut., Mars, the Bush Tetras, the Bloods, Malaria!, Kleenex/LiLiPUT, and latterly Erase Errata, Sonic Youth, Scissor Girls, Karen O, Nisennenmondai etc.

Now: I didn’t include any illustrations with the writing, because my grasp of decent visual art is comparable to Boris Johnson’s grasp of his handlebars after a heavy night out. But apparently it would be nice to have some.

Therefore: I’m looking for suitable images – photographs, illustrations, cartoons – for inclusion in the chapter. Anything relevant considered especially if it pertains to the bands mentioned. Full credit given, further details on request, please pass this on if you can think of anyone who’d care. Thank you.

Also: it is my birthday. I’m going to celebrate with fresh air and daylight.

On Thatcher: Icons and Iron Ladies.

A spectre is haunting London. My daily commute, never a joyful affair, has recently been granted a further dimension of irritation by adverts on buses, hoving into view with tedious regularity, bearing the image of Meryl Streep dolled up as Mrs Thatcher in The Iron Lady. Thirty years on from her rise to power, and after a minor rash of small-screen depictions – Andrea Riseborough in The Long Walk to Finchley, Lindsay Duncan in Margaret – Streep will now portray her on the big screen, the prospect of which I could have happily lived without.

Having as I do firsthand experience of Thatcher’s impact, her government’s break with prevailing consensus and bloody-minded devotion to neoliberal orthodoxies, an objective and rational evaluation of the woman is probably beyond me. That said, her presumably impending death, although I do have a longstanding appointment at a pub in King’s Cross to dutifully raise a glass, is something I’ll be largely indifferent to. It won’t matter. Thatcher as a person has far less bearing on the current world than what she represents. The damage has been done, the battle lost, and much as I might appreciate a Truth and Reconciliation Commission into the 1980s, Thatcher and her co-conspirators are by now too old and whiskey-soaked to be held to any meaningful account.

Efforts to humanise Thatcher, even when they enlist Meryl Streep, seem discomfiting and deeply bizarre. What she means has transcended what she was, is and will be. The purpose of this post, therefore, apart from being an exercise in detachment for me, is to look briefly at some aspects of Thatcher’s image in political and pop culture, the effect of her gender in her role as a woman in power, and her political legacy. Quick, before the next bus goes past.

Musicians and authors in the digital world.

I have an essay in this month’s New Welsh Review on the impact of digitization on publishing as compared to the music industry. I wrote it without anticipating FutureBook’s overview, which does commendable spade-work explaining the situation’s background, present and future, whereas I mostly just snark from the sidelines.

In essence: big publishing houses have, like velociraptors, watched and learned from the music industry’s floundering and are now primed to do better out of e-publishing. My piece also covers the Indelicates’ ‘post-internet’ site Corporate Records, the pros and cons of self-publishing, the unpleasant prospect of e-books becoming the new disposable mass-market paperbacks while physical product becomes concentrated on luxury hardbacks, and why Hodder’s dubious flipback format is the literary equivalent of the MiniDisc.

Perhaps ironically, it’s unavailable online, but the print copy is accessible in all good stockists, or at least all Welsh ones.

Revolting Women, a History.

Written a while back to kick off Bad Reputation’s series on women in protest. Reposting it has mostly reminded me of how fast politics is moving now.

Last winter’s wave of student and youth protests held many points of interest, but one of the most amusing was the Daily Mail’s pearl-clutching front page on what it chose to call Rage of the Girl Rioters, in which it claimed that ‘rioting girls became the disturbing new face of violent protest’. While the article betrayed anxieties about social protest in general, the inclusion of visible female agency occasioned a particularly salacious shock. Continue reading

The outside of everything: a Howard Devoto primer.

Speaking of boredom, let’s start with Tony Wilson’s gloriously earnest and nonchalantly pretentious Buzzcocks/Magazine documentary from 1978. In many ways it seems far longer ago than that, what with girls who work in Woolworths and all that quaint smoking indoors. Don’t make ’em like this anymore, eh? Continue reading

Rare articles that make me want to stand on a chair and throw flowers.

Bravo, Stuart Jeffries, although this piece is about a third too long.

Also, you know what I’m bored of? I’m bored of middle-class pontificators referencing Situationism. It’s a useful analytical tool for any bedroom-bound fourteen-year-old Manics fan (hi!), but give it a rest now, you’re making it about as interesting as dubstep.

God I’m restless.

Ginger snaps: Nicola Roberts, Cinderella’s Eyes

Written for Wears the Trousers 10.10.11.

With Cheryl Cole having reached the apex of her particular fairytale upon her elevation to international pop princess, spare a thought for her Girls Aloud colleagues still at home raking the embers. While Cinderella’s Eyes is by no means a game-changer in the pop world, it succeeds at least in making a more engaging claim to the pop crown than either Cole or Coyle. After a so-so opening with the admirably obnoxious ‘Beat Of My Drum’ and the disjointed ‘Lucky Day’, Roberts lets the veil fall. Listing a litany of woes – her own insecurities, displacement, resentment at being subject to the whims of others, an endless parade of ‘fakers’, mean girls, industry executives, backstabbing, vaulting ambition, superficiality, disingenuousness and the inability to speak openly and honestly – against a relentless, incongruously chirpy off-kilter electro pulse and drum machine pounding, studded with the odd stab at Feminism 101 (“Makeup is make-believe”), it’s like finding extracts from The Bell Jar slipped inside a copy of Heat. Continue reading

Retromania

*

*

*

Amanda Palmer live at Heaven, 02.09.11

Written for Wears the Trousers 08.09.11

*

I’m loath to compare anything to a box of chocolates, but Amanda Palmer gigs do come close. The choice as to what you might get ranges from the likelihood of a soft-centred collaboration with her husband Neil Gaiman, to the slightly bitter aftertaste of something from 2010’s ill-advised Evelyn Evelyn project. Continue reading

Patti Smith, Outside Society

Written for Wears the Trousers 09.09.11

*

The past few years have consolidated Patti Smith’s position as godmother and high priestess among women musicians. Following her induction into the Rock N Roll Hall Of Fame in 2007, last year saw Just Kids, her memoir of life in ’70s New York, receive a National Book Award and a future stage adaptation, and just last week she was awarded the coveted Polar Music Prize by the King of Sweden. Where this leaves her as an artist who once proudly and profanely proclaimed her position “outside of society” is anyone’s guess, but the establishment’s recent embrace of Smith appears to have been the spur for the release of this collection, a primer or sampler of her work aimed, presumably, at those discovering it for the first time. Continue reading

St Vincent, Strange Mercy

Written for Wears the Trousers 30.08.11

*

After her virtuoso debut Marry Me and 2009’s nicely disorientating follow-up Actor, singer and guitarist Annie Clark returns with this itchily anticipated third album. Recorded in her pre-Manhattan hometown of Dallas, Texas, Strange Mercy enlists the assistance of several musicians, including Beck’s musical director Brian LeBarton on keyboards, but Clark has no problem asserting her own musical, lyrical and vocal presence here. Her original concept for the album was to “redefine the idea of the guitar hero, utilising the instrument as a pointillist artist might wield a brush,” and it’s an approach which translates into a glistening, lush and luxuriant listen, full of digital cascades and string-laden crescendos, underpinned by an unsteady percussive stomp. The overall effect evokes a more fragile mid-period Blondie, or Goldfrapp with less of the sledgehammer sleaziness. Continue reading

Why ‘Chav’ is a Feminist Issue.

Chav, n. British slang (derogatory). “In the United Kingdom (originally the south of England): a young person of a type characterized by brash and loutish behaviour and the wearing of designer-style clothes (esp. sportswear); usually with connotations of a low social status.”

– Oxford English Dictionary

1. The C word

If ‘cunt’ is reportedly losing its power to shock or offend, don’t worry, other c-words are available. ‘Class’, for instance, appears to have become unsuitable for use in polite society these days, while ‘Chav’ has never been so commonplace in the respectable parlance of those who would never dream of using any other c-word so blithely. Owen Jones’ book Chavs, a welcome and necessary analysis of the latter phenomenon, identifies it as a culture ‘created and then mercilessly lampooned by the middle-class, rightwing media and its more combative columnists’, and examines the word’s place in current political and cultural discourse in the context of a simultaneous narrowing of socio-economic opportunity. Continue reading

The Raincoats, Odyshape

Written for Wears the Trousers 26.08.11

*

The wave of musical experimentation which took place in the wake of punk generated many new and startling sounds, some of which endured and grew in influence while others became lost to musical history. The Raincoats, a London-spawned, ever-shifting collective based around the partnership of Gina Birch and Ana Da Silva, are now firmly in the former category. Their self-titled debut was described by Vivien Goldman as “the first woman’s rock album” to emerge, its lack of musical or vocal hierarchies or focus-pulling solo virtuosity pioneering an arresting and persuasive kind of rock without the cock. In 1981, Odyshape continued to shift the rules of the game. Continue reading

The Pits and the Pendulum

I’ve had coalmining on my mind recently. Contra last week’s Metro, I don’t think it’s accurate to say ‘the world looked on in despair’ at events at Gleision Colliery – in fact the story was predictably underreported and largely unremarked upon by my usual social media circle, until the story became a self-evidently human tragedy, whereupon it was hardly engaged with at any deeper level than that. Anyway:

As the admittedly lame title of this blog suggests, the coalmine for me is bound up with a certain sense of national identification, but also, if not more so, with class and regional associations. I feel that I have more in common with someone of my age from a post-industrial area in (say) south Yorkshire, than I might with someone from rural west or north Wales or indeed the great bright-lit sprawl that is Cardiff and the Vale. Weighted against this potentially mawkish shoulder-to-shouldering with other unemployment blackspots is the knowledge that this landscape as a functioning entity, as something that defined one as part of and in relation to a certain workforce, as the sum of one’s labour, has (been) altered out of all recognition and what it tends to be seen as generating now is dysfunction. But the mine as a symbol of shared frames of reference carries an inescapable emotional weight. Continue reading

Robots in Disguise, Happiness v Sadness

Written for Wears the Trousers 19.07.11

*

Dee Plume and Sue Denim return with their fourth studio outing, another of the increasing number of albums funded by fans through the Pledge Music scheme. It’s a testament to the enthusiastic loyalty that Robots In Disguise can command that they have a following prepared to keep the faith when the mainstream industry isn’t. And, you know, why should it be? The pseudonymous duo are an intensely idiosyncratic band, still ploughing their furrow of superior electro-punk, with occasional shades of a sharper-toothed, steelier Shampoo, faux-naif femme fatale Claire Grogan, or a Fisher-Price Kills. Their music is curiously compelling more than it is kitsch or cutesy, though, and their chosen personas are insouciant, no-nonsense and utterly unafraid of independence. Continue reading

Girls in Trouble, Half You, Half Me

Written for Wears the Trousers 11.07.11

*

You can argue that the Devil has all the best tunes, but the Bible at least occasionally does a nice line in storytelling. Melodrama and metaphors for human existence pour off the scriptural pages etched in blood and tears. For Brooklyn poet, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Alicia Jo Rabins, stories from the Hebrew scriptures contemplate the complexity of women’s lives in a way that remains relatable today. Her attempt to demonstrate this is Girls In Trouble, an ongoing art-rock project undertaken with her partner and bassist Aaron Hartman, wedding an interest in ancient scriptural stories to expertise in string-led indie and folk-rock. Continue reading

Thea Gilmore, John Wesley Harding

Written for Wears the Trousers 21.06.11

*

Bob Dylan’s seventieth birthday a few weeks back was marked, in part, by reflections on the essentially blokey nature of his observable fanbase. While largely true, this has done nothing to lessen the appeal of his songs as cover material for women from Mae West to Sheryl Crow, not to mention Cate Blanchett’s turn as the man himself in the 2007 biopic ‘I’m Not There’. This re-recording by Thea Gilmore of Dylan’s 1967 album John Wesley Harding then, isn’t a revolutionary move, but not a foolish one either. It follows Gilmore’s performance at a Dylan tribute concert earlier this year, as well as, all the way back in 2002, her acclaimed recording of his ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’. That song appears again on this album, as do guitarist Robbie McIntosh and drummer Paul Beavis, along with Thea’s longterm collaborator, bassist and producer, Nigel Stonier. Continue reading

Emmy the Great, Virtue

Written for Wears the Trousers 14.06.11

There always was more to Emma-Lee Moss than the flimsy whimsy of many of her contemporary dabblers in the rapidly evaporating pool of antifolk. This album confirms that she has greater things to offer. Virtue, written and recorded with Younghusband’s Euan Hinshelwood, released on the band’s own imprint, and financed through the Pledge Music fan-funding scheme, is a very different animal to her 2009 debut, First Love. It’s luxuriantly and smoothly produced, assured and accomplished, its ten tracks forming a cohesive whole in contrast to the debut’s collection of endearingly raw and disparate songs. Continue reading

Sons & Daughters, Mirror Mirror

Written for Wears the Trousers, 13.06.11

Given how quiet they’ve been since 2008′s This Gift, you’d be forgiven for thinking Sons & Daughters had called it a day. Not so. The Scottish quartet are back on the road and back on record this summer with third album Mirror Mirror, a record that not only marks a change in direction for the band but also offers Optimo Music’s JD Twitch his first role as producer, making it something of a gamble. But it’s one that pays off. Continue reading

Never Mind the Bollocks.

Music books written by women, list of. Go, compare, question, critique.

Why don’t more women write about music – or do they? And why don’t more women write about Dylan? It can’t just be me and Sady Doyle.

Also, with due apologies for more self-promotion – I don’t think I’ve mentioned this here yet, but I’m currently writing a chapter on female postpunk musicians for a forthcoming anthology on that shy and elusive creature, the girl band. This book will be a contender with or without my contribution though. Watch this space.

In Defence of Rihanna’s ‘Man Down’.

Written for Bad Reputation, 8.6.11

*

Another week, another women-in-music controversy, and another hotly debated video from Rihanna. Having ticked domestic violence and sadomasochism off the musical list, she’s responded to recent accusations of being a major player in the oversexualisation of pop by upping the ante, making her latest offering a blend of sexual violence and violent retribution. The video for Man Down, which opens with Rihanna shooting a man who is later revealed to have assaulted her after they dance at a club, has kicked up a predictable media dustcloud. It’s all a far cry from ‘Pon de Replay’. Continue reading

FLOOD THEATRE: aprés-moi, le deluge.

Laughter in dark times becomes necessary, providing both critique and consolation. And the nights are certainly drawing in. I mean, look at all this. Or, on what seems by comparison a light note, this surreal attempt to humanise the employees of an organisation geared solely towards turning a profit by trading in hatred and tits.

Satire has never seemed so conspicuous by its absence. It is one thing to see corruption, incompetence and venality occasionally exposed; it is quite another to see so many practitioners of corruption, incompetence and venality incessantly expose themselves with the bafflingly brazen insouciance of compulsive flashers drunk in a town park. So the news has turned horribly, endlessly funny – far funnier than any current attempt to dissect or diagnose its disgustingness. Look at this, or this, or the point at which the dark arts of spin, the erosion of journalistic enquiry, and the vacuum at the heart of the Labour Party coalesced to form a revelatory moment of pantomime androidry – and how quaint, how nearly comforting, how spot-on then but now unremarkable those past satirical visions seem, eh?

The lunatic reality of contemporary politics is galloping ahead of satire by significant furlongs, and few seem capable of or even interested in catching up. Which is where Flood Theatre come in.

Flood takes all the above into account, and styles itself ‘the new comedy for the new politics’. In soundscapes and sketches drawn with a dramatic flair for language and a fine sense of the absurd, it outlines our rats’ nest of politics, media and society with unflinching precision.

There’s a long and noble history of art that takes life in all its grim, bleak splendour and manages to wring out disbelieving laughter. There’s been Chris Morris, there is Stewart Lee, and, soon, there will be Flood.

Flood perform at the Edinburgh Fringe, August 5th-27th. Book now.

Can Adele and her Marketing Men change the face of Women in Music?

Written for Bad Reputation, 1.6.11

*

Poor old millionaire superstar Adele, eh? No sooner has the dust settled on the furore over her objections to being a higher-rate taxpayer, than she gets thrown into the vanguard of another of those putative Real Women in Music revolutions. A mere three years after she started out, and after just seventeen weeks of her second album at Number One, it appears to have suddenly dawned on Richard Russell that Adele exemplifies all that’s healthy and hopeful in the otherwise dire and overheated state of contemporary pop. Continue reading

Death of a Good Pub.

Some of my juvenilia, from when I lived south of the Thames. I wrote this in 2005 for the much-missed marvel that was Smoke, A London Peculiar, and I was inspired to dig it up by reading this post on Transpontine, the compendium of south-east London life. It’s an elegy on my favourite ex-pub in London, which I still miss. Now only the Montague Arms keeps a remnant of the dream alive.

*

Number one on absolutely no one else’s list of Good London Pubs is the sadly defunct Goldsmiths Tavern. When I lived in New Cross as a student I didn’t go near this place for months – it was open past 2am but was extremely dodgy in look and reputation, you heard various stories about plans hatched and deals done that would’ve made Guy Ritchie come on the spot. Continue reading

The Indelicates, David Koresh Superstar

Written for Wears The Trousers.

Go go Corporate Records.

*

The word ‘provocative’ retains about as much meaning in contemporary art as the word ‘revolutionary’, but I’d still like to think that the Indelicates’ latest enterprise deserves more than a wearily raised eyebrow. Earnest, arch and irreverent by turns, their concept album on late cult leader David Koresh and the 1993 Waco siege is an achievement along the lines of Luke Haines’ Baader-Meinhof or Jerry Springer the Opera, and while I realise that only a certain demographic will regard that as a ringing endorsement, it is. Continue reading

Madam, Gone Before Morning

Written for Wears the Trousers.

*

You might recognise Sukie Smith from various acting roles, but her background on the small screen has little bearing on the widescreen feel of her current musical project. Madam are a six-piece band fronted and produced by Smith, and this is their second release after 2008’s In Case of Emergency. Smith is an accomplished composer who provided the music to the 2007 thriller Hush Your Mouth, and much of this album has the air of a similar kind of film score. The album’s title is indicative of its overall atmosphere: it brims with clandestine deeds done under cover of darkness, cryptic confessions, and regretful departures pre-sunrise. Continue reading

Philip Roth wins the Booker Prize: Carmen’s Complaint

A now outdated post written for Bad Reputation.

Philip Roth is a good writer, but I wouldn’t want to shake hands with him.

– Jacqueline Susann’s verdict on Portnoy’s Complaint

Last week was a busy week in the book world. Sainsburys found itself anointed Bookseller of the Year to the chagrin of actual booksellers, the beleaguered Waterstones chain was saved from the asset-stripping abyss, and the Man Booker International Prize went to the veteran novelist Philip Roth. The last of these events made the biggest splash in the mainstream press, due to the consequent resignation in protest from the judging panel of Carmen Callil, the redoubtable founder of Virago Press, who – cue shock, horror, and the frantic ordering by booksellers of Roth’s backlist – disparaged Roth as a writer and disputed his worthiness to win. Continue reading

Lupen Crook, Waiting for the Postman

Whenever I listen to a lot of Lupen Crook songs I can’t help (affectionately) picturing Poor Tom, the displaced nobleman in the guise of a beggar capering upon the blasted heath in King Lear. I realise this is unfair to Mr Crook aesthetically and stylistically, and in any case has hardly happened at all while listening to his latest. Home-produced and recorded in the months just before spring, Waiting for the Postman is a still and contemplative record of domestic claustrophobia, comedown and loss and their ultimate transcendence.

‘The Domestic’, low and lugubrious, starts things on a bitter and hard-bitten note, but the album’s darkly groovy self-laceration – heartbreak and paranoid withdrawal on ‘Cold Alone’, fame anticipated as soul-sucking pull on ‘Tale of an Everyman’ – is leavened with rippling rainy-afternoon melancholy and gently melodic reflections on friendship, love and their loss. ‘Chasing Dragons’, heartfelt and warm, is straightforwardly gorgeous. So is ‘Where the Crow Flies’, so is ‘Arts and Crafts’, and so is the intricately self-referential ‘A Little More Blood on the Tracks’ (and the chutzpah of giving it that title, unusually, didn’t even tickle my Dylanist gag reflex). ‘Hard Times’ is some kind of madly gleaming apocalyptic eurodisco that’s worth the price of admission by itself.

Just an all-round awesome album. This record sounds like a long-held breath let out, like the aftermath of trauma, and it feels like balm applied to wounds.

*

Lupen Crook, Waiting for the Postman is available here.

Libraries Gave Us Power: notes on the Manic Street Preachers and class

So I liked Owen Hatherley’s piece on Pulp, and I knew reading the comments would spoil it all, but reader, I read them. The majority were bafflingly wet-blanket in nature, wildly and wilfully missing the article’s point, if studded with bits of valid and interesting discussion. Specifically, though, I was surprised to encounter in both the article and the responses a lack of any mention of Manic Street Preachers. Surely you can’t reach back into the 90s, grasping for lines to describe the sociopolitical here and now, without burning your fingers on the white-hot irony of ‘A Design for Life’?

‘We don’t talk about love,

We only want to get drunk

And we are not allowed to spend

As we are told that this is the end’

If Pulp were the last art-school band (and I’m by no means convinced of that), then surely the Manics were the last artistic gasp of a certain breed of late 20th-century industrial working class? Continue reading

Holly Golightly & The Brokeoffs, No Help Coming

Written for Wears the Trousers.

*

Holly Golightly – real name, no gimmicks – has worn a variety of hats in her almost twenty years as an iconic and inspirational recording artist, taking in styles from three-chord garage to R&B. Since 2007 her chosen outfit has been Holly Golightly & The Brokeoffs, a country-infused collaboration with her longtime bandmate Lawyer Dave. Continue reading

Stop me if you think that you’ve heard this one before.

Simon Reynolds has decently condensed his new ‘un into a Guardian article:

The book is not a lament for a loss of quality music – it’s not like the well-springs of talent have dried up or anything – but it registers alarm about the disappearance of a certain quality in music: the “never heard this before” sensation of ecstatic disorientation caused by music that seems to come out of nowhere and point to a bright, or at least strange, future.

I don’t wish to dollop even further layers of irony on top of this particular trifle – but we’ve been here before, too, haven’t we? This is repetition, if not revival. What Reynolds castigates as ‘retromania’ has been sporadically identified throughout the past decade, most perspicaciously by several of my mates around about the point at which the third pint starts to make its presence felt, because we’re old enough to remember when revivals seemed novel, if only because this was the first we’d heard of them. Continue reading

Offcuts (The Indelicates, David Koresh Superstar)

My review of the new Indelicates album is now up at WTT. I couldn’t find a non-clunky way of including the fact that Jim-Bob of moderate Carter USM fame is on it, singing the part of Timothy McVeigh. So, uh, he is, and he does it well.

One thing which didn’t really merit a mention in the review is that the opening lines to ‘Ballad of the ATF’ fit perfectly with the opening lines of ‘Bad Romance’, which gives me a disconcerting mash-up of both in my head every time I hear either.

I also excised a paragraph of dubious necessity which ended: ‘You’d have to be an idiot to take offence at anything on this record. But as the aspiring Congressman said, there’s an awful lot of idiots out there and don’t they deserve some representation?’

And I took out the description of a particular vocal as ‘a crystalline vessel belying the bitter draughts it can contain’, because reading that back was making me want to put my own head down the toilet and flush the chain.

This album, though, go get it.

On liking American Psycho.

In 1874, Samuel Clemens called Ambrose Bierce’s latest effort The Vilest Book in Print, writing that ‘…for every laugh that is in his book there are five blushes, ten shudders and a vomit. The laugh is too expensive.’ I mean, it’s anyone’s guess what Samuel Clemens might have made of Bret Easton Ellis. Continue reading

How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bo(m)b

So the next scheduled Apocalypse isn’t until October. Good; I have stuff to do before October, but little to do after it, and at the current rate of Armageddon I won’t need to pay off my student loan. More importantly, Dylan was 70 on Tuesday.

One of my favourite theories/lies/facts about Dylan is that the lyrics to ‘It’s a Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall’ consist of titles or opening lines for other songs which Dylan felt he wouldn’t have time to write before nuclear conflagration moved these matters rather lower down everyone’s list of concerns. In similar manner – and because I’m quite aware that most of my writing is what you’d get if you fed ‘The Libertines’, ‘class war’, ‘wank’, ‘appalling pun’, and ‘cultural history’ into a Random Lyrics Generator – here is a blog post consisting of titles for other blog posts which I doubt I’ll ever get around to writing. Only about two of these are serious proposals, of course, and the rest self-parodic. But the two keep changing. Continue reading

Diminishing gigs and gigs of diminishing return.

There are times when I think that readers of this blog are simply bearing witness to the Orwellian tragedy of someone once boundlessly enthusiastic about live music slowly having it ground out of them by the suspicion that I’d be better off reading a book than spending yet another evening squashed, skint and bored in Camden while some overindulged former public schoolboy vomits down a microphone, but oh well, on with the motley.

I was sorting through some things last night – ticket stubs, diaries, anal-retentively compiled whathaveyou – and look, these are all the gigs I went to in 2004, back when Dirty Pretty Things was still a club night named after a Stephen Frears film rather than a by-word for frustratingly pedestrian musical spin-off projects:

Oh bondage, no more.

Jesus, it’s been a bad week. 53 is no age.

This is my favourite X-Ray Spex song:

Oh, negative: The Kills, Blood Pressures

It’s been three years since the sparsely angular stylings of Midnight Boom, and even longer since the garagey growl of their early work, but the transatlantic partnership of Alison Mosshart and Jamie Hince has survived the former’s sojourn among The Dead Weather’s demon blues to produce what the duo describe as their most ambitious and accomplished recording to date.

A lot of people won’t get no justice tonight.

Cards on the table: I am a (very) former Labour Party member, a former unaligned-far-left hack, a former student politician, and a current jaded burn-out who’s more or less lost the faith. What I’ve regained since the last election is not the faith but the fear. Seeing this government use the excuse of debt reduction to conduct a sustained assault on the welfare state’s structures and foundation is not something I can stand by and watch. The question, as ever, is how to express this opposition. Saturday saw a TUC-organised official march, fringed with unofficial peaceful protests and unofficial direct action. The discourse after demonstrations is always varying degrees of unhelpful and unrepresentative, as reportage and analysis splinter into shards of individual experience, each of which reflect only a portion of the whole. This is in no way a contribution to ongoing debate, it is merely my own record and reflection.

The black bloc on Saturday was by some accounts the biggest since J18, which made me think that, as I’ve said before, what’s happening now seems like not a revolution but a return to the protests to which I was introduced over a decade ago – the days of carnivalesque anticapitalism and reclaiming the streets. That said, I think our critique of capitalism in the early 2000s was certainly more vague, still post-Cold War, appealing more to globalising and internationalist issues of social justice and civil liberties because less immediately rooted in financial crisis – and perhaps, for the same reasons, less last-ditch and desperate than it currently seems. I don’t know, and to have a clearer idea, I’d have to get out there and see for myself.

I didn’t do a great deal of Getting Out There on Saturday. I remained with a small group of disparately aligned friends and family, massing outside Embankment tube and then crawling through Waterloo and Westminster. There were an awful lot of us. There were gorgeous trade union banners which had seen action throughout the past century. There were Banksy-esque stencils of Clement Atlee’s image. There were official placards manually-adjusted to call Nick Clegg a variety of entirely-deserved things. The Bloody Hell, That Must Have Taken Ages prize goes jointly to those carrying the huge black cube representing the income of the highest percentile of earners, to which was attached far smaller red cubes showing the relative size of the average income (I think), and those driving the miniature tank playing the theme from The Great Escape. Both of these were the best things I’d seen on a protest since the enormous papier-maché bomb labelled ‘structural readjustment’.

The only demo of comparable size I can remember – where the front of the march had walked the length of the route and reached its destination while more people were still at the back of the march, waiting to move off – was the big Iraq protest in 2003. Then as now, those marching were not homogenous, came from all over the country, and held no obvious signs of slavish adherence to the Labour leadership. Nor did I feel alone in lacking both faith in parliamentary process and any burning desire to stand for hours in Hyde Park listening to hackneyed whistling-up from the stage. Hence, by the time of our stop-off in Trafalgar Square, I opted for the pub. When the revolution comes, shoot me.

The Chandos crouches just off Trafalgar Square, and used to be the post-rally destination of most of my comrades whenever we ended up in the vicinity, largely because, unlike many pubs on or near the route of demonstrations, it had no sign on the door banning work-boots, banners and/or placards. Once inside, an illustration of how far I’ve fallen since the early 2000s was provided by there being no one I knew there apart from my old politics lecturer, who failed to recognise me, as indeed he had during most of my time at Goldsmiths. At the bar I got talking to a bloke who, like me, was a veteran of 2003’s enormous anti-war march, to which he had taken his 12 year old daughter. According to him, she’d said, impressed by the turnout, ‘they’ll have to listen to us now, won’t they?’

He told me this and rolled his eyes, as though aware of how mawkish and implausibly convenient an ending this might make to a subsequent spiel on the pointlessness of peaceful protest. But honestly, fuck irony. Politics in the last few years has got so blatantly contemptuous, so transparently indifferent, that I doubt any kid on the march on Saturday would have had that degree of faith in people power.

The Monday after the march, back at work in Soho, I went out to see the damage done. Little trace remained beyond some indistinct scrawlings on the boarded-up HSBC on Cambridge Circus and, further up the sidestreets, a circled-A in pink spraypaint on a couple of flaking black litter-bins. The slogans written on the scaffolding outside Central St Martins – ‘Make the banks pay’, ‘ACAB’, were at least making more of a stab at focused oppositional discourse. Yesterday lunchtime, more than a week on, the slogans on HSBC were invisible under daubs of white paint, the bank was open for business as usual and pretty soon the West End will look, and feel, as though nothing ever happened.

Am I glad I marched? Yes, of course. And I’m still unaligned, and I reject the notion that my lack of a membership card matters. March 26th wasn’t an attempt at revolution, and was more than a bid for space on the front page, and more than an exercise in branding. It was an act of solidarity, an attempt to demonstrate to all who watched and all who took part that no one is alone in opposing the actions of this government. And it did that, even if that’s all it did.

Des Ark, Don’t Rock the Boat, Sink the Fucker

Without wishing to damn with faint praise, Des Ark are very good at titles. Despite the rule about not judging a book by its cover, Don’t Rock The Boat, Sink The Fucker is a statement of militant intent which almost inevitably leads to expectations of a harder-edged musical style. Frontwoman Aimee Argote has long been steering an inconsistent course between post-punk, Appalachian folk and blistering blues-rock, and likes to keep the listener guessing. But any hopes or fears for a more aggressive direction get neatly overturned as soon as opening track ‘My Saddle Is Waitin’ (C’mon Jump On It)’ announces itself with tremulous chimes and a delicate shimmer of strings.

10 O’Clock Live: Three Men and a Little Lady?

Seen Ten O’Clock Live, then? …Yeah. Breathlessly billed as Britain’s answer to the Daily Show, a return to the satirical standard set by 1962’s groundbreaking That Was The Week That Was and the grand guignol glory days of Spitting Image, with hype like that the show was perhaps doomed to fall short of expectations.

All Quiet on the First Great Western Front

Last week I returned to the Old Country – well, not the Old Country itself, but rather Cardiff, my land’s increasingly swish and cosmopolitan capital, with its rapaciously expanding shopping-and-eating quarter and its incongruous postmodern street sculptures making it feel a bit like a Torchwood theme park. The second most immediately notable thing about Cardiff at the minute is the preponderance of Emo kids there. I know Emo hit the subculturally-attuned youth of south Wales hard, but that was some years previously, and I was aghast to discover that the wretched thing still holds much of the city in its terrible, slappable, Lego-fringed grip. Will we never be set free?

This weekend I’m going to Southampton to be a superstar DJ. By which I mean, to hand over some mix CDs and hope for the best. I hope you all have good weekends; here are some curios to take you into it. Continue reading

Women, Men, and Music: the XY Factor

Let me begin with some residual New Year bonhomie by saying that the New Yorker‘s Alex Ross is not the problem here. It’s just that you sometimes need to take an inventory of the symptoms before starting on the cause. Last month I attended a talk by Ross on the release of his latest book. The talk and the discussion which followed were interesting enough, but throughout the evening I couldn’t help noticing that, although there were several women in attendance, every single raised voice in the room was male.

Father, Ruler, King, Computer: alternative Valentines playlist redux

In recent days, the search terms leading the unwary googler to this place have heavily featured the words ‘alternative valentines playlist’. I did one of these last year, and, self-evidently, haven’t done another since. I have re-uploaded the file from last year’s post though, so if that’s what you’re after, it’s here: Happy Highly-Expensive Chocolate Day.

But what, pray, do you want with googling ‘alternative valentines playlist’ and variations thereon? Are you going to snaffle this playlist for substance or suggestion? Make your own, Madam: your other half is totally going to appreciate your own playlist more than one you downloaded from the bitterest Howard Devoto obsessive on WordPress. And if you don’t have another half, then I’m frankly baffled to learn that you spend your time doing anything other than making playlists and then playing them. I know I don’t.

Shilpa Ray & her Happy Hookers, Teenage & Torture

In music writing as elsewhere, shortened attention spans and a craving to be spoonfed have led to the unfortunate development of lazily reductive shorthand, enabling a user-friendly pitch of a particular artist even as it simplifies and undervalues their complexity. Hence Amanda Palmer’s pigeonholing as kooky cabaret diva, Nicki Minaj as cartoonish pocket Missy, and Shilpa Ray as whiskey-soaked wildwoman, when they’re all more interesting than that. Sure, Teenage & Torture, like 2009 debut A Fishhook An Open Eye, has the requisite blues-rock base and throat-shredding vocal superstructure to justify this stylistic categorisation, but the Mad Bad Girl tag is particularly pernicious. It’s a comforting label that makes sense of the discomforting, allowing, in this case, Ray’s rage-fuelled dissections of feminine ideals, sexual mores and consumer culture to be glossed as hysterical spectacle. The more we exoticise a performer as irrational and unfamiliar, the less valid and identifiable in our everyday surroundings we render her concerns and accusations.

Oi! to the World: Blaggers ITA, ‘The Way We Operate’

Following my attempted rehabilitation of S*M*A*S*H, here is another song snipped from the forgotten High Agitation Pop tapestry of 1990s Britain, to which I haven’t listened for a good ten years.

Oh, remember Agit-Pop? Remember when mixing punk with hip-hop and electronica in the name of antifascism seemed like a good idea? Remember Blaggers ITA? Their Wiki helpfully did-you-knows that ITA is ’90s slang for “in the area”‘, which I didn’t in fact know at the time. There you are, that’s the 1990s for you: we made the word ‘here’ two words longer, then we developed an acronym for it.

I discovered Blaggers ITA via their short-lived support slot on the Manic Street Preachers’ 1993 tour. This was curtailed amid controversy over their singer having allegedly lamped a journalist over an alleged accusation of his past, intensely regretted, involvement with the far right. (I’m always less shocked than perhaps I should be by the number of people who switch political extremes, starting off by, when young, channelling frustration and resentment through a right-wing filter before seeing it for the repugnant sham it is. A similar trajectory was taken by the young Ricky Tomlinson, whom I like less than I like the late Matty Blagg. Maybe that’s because Tomlinson went on to do The Royle Family, which gradually decayed into a pseudo-sentimental piece of confected class voyeurism, whereas by contrast the 1991 Blaggers effort Fuck Fascism, Fuck Capitalism, Society’s Fucked is perhaps the best lairily succinct summation of a certain late twentieth-century mindset we’re likely to get.)

Anyway, ‘The Way We Operate’ was a response to the racially-inflamed brutalization of Rodney King by Los Angeles police in 1991, and the riots which convulsed that city the following year after the defendants’ acquittal by an all-white jury. It mixed televised reportage and calls to arms with guitars that swirl like circling news helicopters, riffing on Public Enemy’s ‘Burn Hollywood Burn’ and segueing the admirable internationalism of ‘West Belfast, Brixton, Broadwater Farm, Soweto, East LA – it’s all the same thing’ into its inanely earnest chorus.

Don’t write ‘em like that anymore, do they? Not a great song, maybe. But with most of popular culture – comedy, tv, literature as well as music – currently punching downwards when it punches at all, I find it helps to be reminded that songs can have worthier targets. Even if these days this sort of thing could almost be described as fucking quaint.

If You’ve Never Then You Ought: Half Man Half Biscuit

My belated Christmas present to you all, in the dead days before New Year, is the recommendation that you get into Half Man Half Biscuit, if you haven’t already. After five or so years of listening to their back catalogue I don’t have a particular song to recommend, but I recommend you discover your favourite yourself.

Many bands polarise opinion; with ‘The Biscuit’ (as absolutely no one outside the febrile hive-mind of the Guardian weekend supplement calls them) it’s more that people divide into those who think they might like them, and consequently do, and those who think they won’t like them and never give themselves the opportunity to discover how wrong they are.

Always a risky business, innit though, ‘comedy’ in music. I don’t know how I’d class HMHB – as comedy goes, they’re more Chris Morris than Carry On, although they’re as quintessentially British as both. They skewer pretension in all its forms – sometimes satirically, sometimes whimsically, sometimes with nailed-on bleak observation of the nation’s corpse picked clean. But there’s a lot more to them than sneering, and a hell of a lot more than self-conscious zaniness. They’re not, as their detractors often presume, the musical equivalent of that bloke in your office who thinks that owning a novelty tie and a mug with a ‘comedy’ slogan makes up for having a wit and charm deficit the size of the national debt – in fact, they’ve probably written a song about him. They also provide, more or less, a running commentary on the spiralling absurdities of the British music scene.

Their lyrics are studded with nods to Thomas Hardy, and their music is often wickedly parodic. They are much, much cleverer than you think. Nigel Blackwell employs the Birkenhead accent’s capacity for dry disdain building to banked fury in a manner only bettered by Paul O’Grady’s anti-Tory tirade last October. In a sane and well-ordered world, Nigel Blackwell would already have turned down the post of Poet Laureate.

Just occasionally, this band make me feel alright about the world and my place in it. Happy new year.

I’ve also half-inched my new tagline for 2011 from them – the old one was getting me an alarming number of hits from bemused Nietszsche enthusiasts.

Gaye Advert and the Great Cock ‘n’ Balls Swindle

‘Sexuality in Rock’n’roll is one more area weighed down heavily by its history and language. While none could or should deny the aspects of sexual interest and thrill inherent in live music, the performance space is problematically male-dominated.’ – Ian Penman, NME, 1979

‘I really wish that I’d been born a boy; it’s easy then ’cause you don’t have to keep trying to be one all the time.’ – Gaye Advert, 1977

Women in bands, when under the media spotlight, often find themselves swindled out of due credit by virtue of their gender. If they’re not being accused of clinging to the coattails of their backing boys to disguise their own lack of musical ability, they’re being judged on their aesthetic appeal to the exclusion of anything more relevant. It’s disappointing to observe how ubiquitously this principle applies. Even in the midst of punk, as girls picked up guitars, bass, and drumsticks, taking the stage alongside boys as more than cooing vocalists or backing dancers, they attracted that lethal combination of critical suspicion and prurient interest.

I love punk partly for the number and variety of women it involved and the freedom of expression it offered them. I loved X-Ray Spex – a Somali-British teenage feminist demagogue whose vocal screech swooped like a bird of prey over twisting vistas of saxophone. I loved the Slits and their slippery, shuddering dub-punk hymns to the tedium of sex and the joys of shoplifting. And I loved Gaye Black, bassist for The Adverts and widely regarded as punk’s first female star.

Continue reading

Sunday Service: ‘Twas the Riot Before Christmas

If you’re an easily suggestible sort, the last few weeks’ flurry of alarmist headlines on strikes, snow, and student riots might lead you to think of London as the convulsing epicentre of the end of the world as we know it. In fact, it’s still perfectly possible to work and play on the streets of the capital without detecting any signs of the collapse of civilisation, although that doesn’t mean they aren’t there.

A King of Shreds and Patches: Lupen Crook, The Pros and Cons of Eating Out

The Medway Towns, just far enough away from London for it to matter, have sheltered this country’s conscientious contrarians from Charles Dickens to Billy Childish. The Pros and Cons of Eating Out is the third album from the Kent Delta’s current wandering minstrel, Lupen Crook.

I hesitated over that ‘wandering minstrel’, you know, in case the description was fast becoming a cliché (or had, I don’t know, been copyrighted by Frank Turner). If that other frequently pigeonholed troubadour, Patrick Wolf, has reportedly considered changing his name to “please use a thesaurus or a brain to find another word for ‘flamboyant’ Patrick Wolf”, I wonder if, in time, Lupen Crook might end up requiring similar measures to get rid of the wandering minstrel tag.

Not that it’s an inappropriate or unhelpful label – much of Crook’s artistic strength does lie in a picaresque sense of threadbare and ramshackle rootlessness, a commitment to collectivism, a DIY approach to distribution and a palpable desire to entertain.